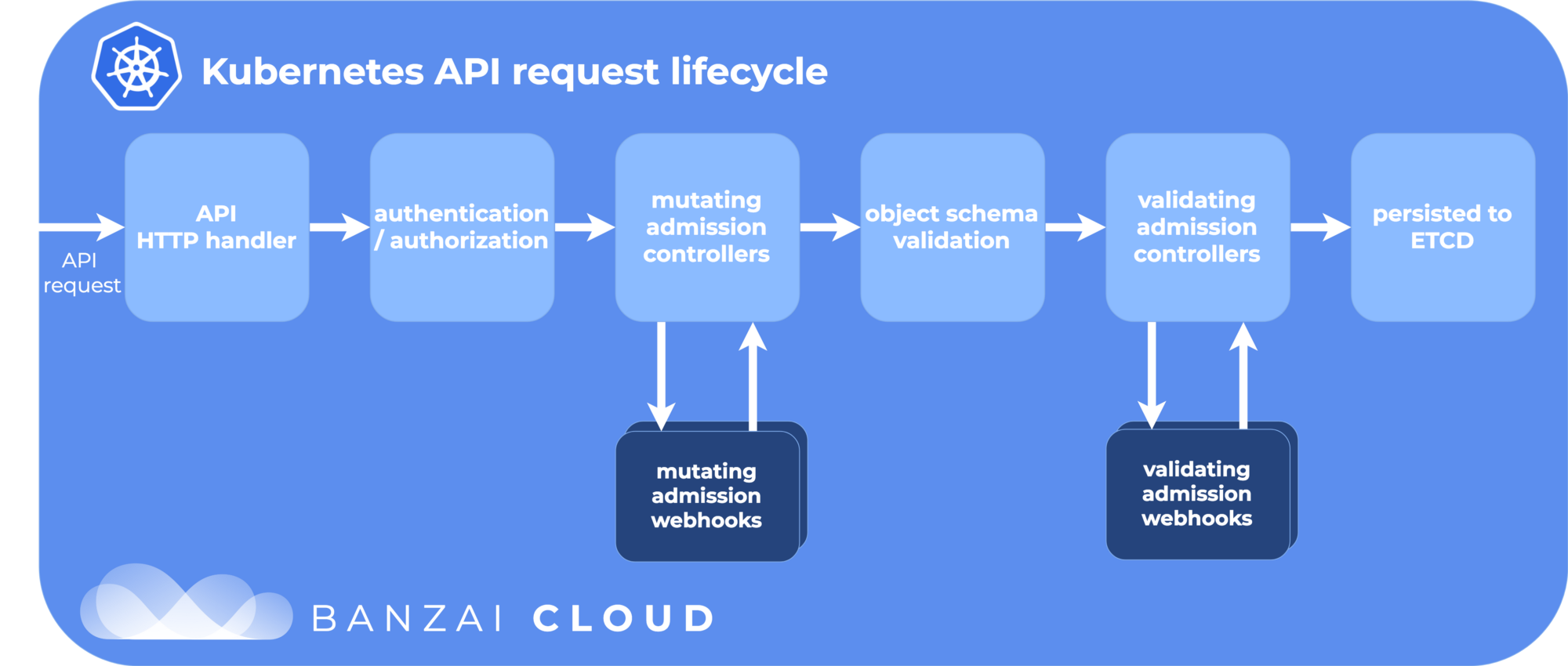

class: title, self-paced Jour 4<br/>Kubernetes Avancé<br/> .nav[*Self-paced version*] .debug[ ``` ``` These slides have been built from commit: 86828ca [shared/title.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/title.md)] --- class: title, in-person Jour 4<br/>Kubernetes Avancé<br/><br/></br> .footnote[ **WiFi: CONFERENCE**<br/> **Mot de passe: 123conference** **Slides[:](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h16zyxiwDLY) http://2020-02-enix.container.training/** ] .debug[[shared/title.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/title.md)] --- ## Intros - Hello! We are: - .emoji[🐳] Jérôme Petazzoni ([@jpetazzo](https://twitter.com/jpetazzo), Enix SAS) - .emoji[☸️] Julien Girardin ([Zempashi](https://github.com/zempashi), Enix SAS) - The training will run from 9am to 5:30pm (with lunch and coffee breaks) - For lunch, we'll invite you at [Chameleon, 70 Rue René Boulanger](https://goo.gl/maps/h2XjmJN5weDSUios8) (please let us know if you'll eat on your own) - Feel free to interrupt for questions at any time - *Especially when you see full screen container pictures!* .debug[[logistics.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/logistics.md)] --- ## A brief introduction - This was initially written by [Jérôme Petazzoni](https://twitter.com/jpetazzo) to support in-person, instructor-led workshops and tutorials - Credit is also due to [multiple contributors](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/graphs/contributors) — thank you! - You can also follow along on your own, at your own pace - We included as much information as possible in these slides - We recommend having a mentor to help you ... - ... Or be comfortable spending some time reading the Kubernetes [documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/) ... - ... And looking for answers on [StackOverflow](http://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/kubernetes) and other outlets .debug[[k8s/intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/intro.md)] --- class: self-paced ## Hands on, you shall practice - Nobody ever became a Jedi by spending their lives reading Wookiepedia - Likewise, it will take more than merely *reading* these slides to make you an expert - These slides include *tons* of exercises and examples - They assume that you have access to a Kubernetes cluster - If you are attending a workshop or tutorial: <br/>you will be given specific instructions to access your cluster - If you are doing this on your own: <br/>the first chapter will give you various options to get your own cluster .debug[[k8s/intro.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/intro.md)] --- ## Accessing these slides now - We recommend that you open these slides in your browser: http://2020-02-enix.container.training/ - Use arrows to move to next/previous slide (up, down, left, right, page up, page down) - Type a slide number + ENTER to go to that slide - The slide number is also visible in the URL bar (e.g. .../#123 for slide 123) .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- ## Accessing these slides later - Slides will remain online so you can review them later if needed (let's say we'll keep them online at least 1 year, how about that?) - You can download the slides using that URL: http://2020-02-enix.container.training/slides.zip (then open the file `4.yml.html`) - You will to find new versions of these slides on: https://container.training/ .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- ## These slides are open source - You are welcome to use, re-use, share these slides - These slides are written in markdown - The sources of these slides are available in a public GitHub repository: https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training - Typos? Mistakes? Questions? Feel free to hover over the bottom of the slide ... .footnote[.emoji[👇] Try it! The source file will be shown and you can view it on GitHub and fork and edit it.] <!-- .exercise[ ```open https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/master/slides/common/about-slides.md``` ] --> .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Extra details - This slide has a little magnifying glass in the top left corner - This magnifying glass indicates slides that provide extra details - Feel free to skip them if: - you are in a hurry - you are new to this and want to avoid cognitive overload - you want only the most essential information - You can review these slides another time if you want, they'll be waiting for you ☺ .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- class: in-person, chat-room ## Chat room - We've set up a chat room that we will monitor during the workshop - Don't hesitate to use it to ask questions, or get help, or share feedback - The chat room will also be available after the workshop - Join the chat room: [Gitter](https://gitter.im/enix/formation-highfive-202002) - Say hi in the chat room! .debug[[shared/about-slides.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/about-slides.md)] --- name: toc-chapter-1 ## Chapter 1 - [Network policies](#toc-network-policies) - [Authentication and authorization](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-chapter-2 ## Chapter 2 - [Stateful sets](#toc-stateful-sets) - [Running a Consul cluster](#toc-running-a-consul-cluster) - [Local Persistent Volumes](#toc-local-persistent-volumes) - [Highly available Persistent Volumes](#toc-highly-available-persistent-volumes) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-chapter-3 ## Chapter 3 - [Resource Limits](#toc-resource-limits) - [Defining min, max, and default resources](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) - [Namespace quotas](#toc-namespace-quotas) - [Limiting resources in practice](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) - [Checking pod and node resource usage](#toc-checking-pod-and-node-resource-usage) - [Cluster sizing](#toc-cluster-sizing) - [The Horizontal Pod Autoscaler](#toc-the-horizontal-pod-autoscaler) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] --- name: toc-chapter-4 ## Chapter 4 - [Collecting metrics with Prometheus](#toc-collecting-metrics-with-prometheus) - [Centralized logging](#toc-centralized-logging) - [Extending the Kubernetes API](#toc-extending-the-kubernetes-api) - [Operators](#toc-operators) .debug[(auto-generated TOC)] .debug[[shared/toc.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/toc.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-network-policies class: title Network policies .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-1) | [Next section](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Network policies - Namespaces help us to *organize* resources - Namespaces do not provide isolation - By default, every pod can contact every other pod - By default, every service accepts traffic from anyone - If we want this to be different, we need *network policies* .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## What's a network policy? A network policy is defined by the following things. - A *pod selector* indicating which pods it applies to e.g.: "all pods in namespace `blue` with the label `zone=internal`" - A list of *ingress rules* indicating which inbound traffic is allowed e.g.: "TCP connections to ports 8000 and 8080 coming from pods with label `zone=dmz`, and from the external subnet 4.42.6.0/24, except 4.42.6.5" - A list of *egress rules* indicating which outbound traffic is allowed A network policy can provide ingress rules, egress rules, or both. .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## How do network policies apply? - A pod can be "selected" by any number of network policies - If a pod isn't selected by any network policy, then its traffic is unrestricted (In other words: in the absence of network policies, all traffic is allowed) - If a pod is selected by at least one network policy, then all traffic is blocked ... ... unless it is explicitly allowed by one of these network policies .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Traffic filtering is flow-oriented - Network policies deal with *connections*, not individual packets - Example: to allow HTTP (80/tcp) connections to pod A, you only need an ingress rule (You do not need a matching egress rule to allow response traffic to go through) - This also applies for UDP traffic (Allowing DNS traffic can be done with a single rule) - Network policy implementations use stateful connection tracking .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Pod-to-pod traffic - Connections from pod A to pod B have to be allowed by both pods: - pod A has to be unrestricted, or allow the connection as an *egress* rule - pod B has to be unrestricted, or allow the connection as an *ingress* rule - As a consequence: if a network policy restricts traffic going from/to a pod, <br/> the restriction cannot be overridden by a network policy selecting another pod - This prevents an entity managing network policies in namespace A (but without permission to do so in namespace B) from adding network policies giving them access to namespace B .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## The rationale for network policies - In network security, it is generally considered better to "deny all, then allow selectively" (The other approach, "allow all, then block selectively" makes it too easy to leave holes) - As soon as one network policy selects a pod, the pod enters this "deny all" logic - Further network policies can open additional access - Good network policies should be scoped as precisely as possible - In particular: make sure that the selector is not too broad (Otherwise, you end up affecting pods that were otherwise well secured) .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Our first network policy This is our game plan: - run a web server in a pod - create a network policy to block all access to the web server - create another network policy to allow access only from specific pods .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Running our test web server .exercise[ - Let's use the `nginx` image: ```bash kubectl create deployment testweb --image=nginx ``` <!-- ```bash kubectl wait deployment testweb --for condition=available ``` --> - Find out the IP address of the pod with one of these two commands: ```bash kubectl get pods -o wide -l app=testweb IP=$(kubectl get pods -l app=testweb -o json | jq -r .items[0].status.podIP) ``` - Check that we can connect to the server: ```bash curl $IP ``` ] The `curl` command should show us the "Welcome to nginx!" page. .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Adding a very restrictive network policy - The policy will select pods with the label `app=testweb` - It will specify an empty list of ingress rules (matching nothing) .exercise[ - Apply the policy in this YAML file: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/netpol-deny-all-for-testweb.yaml ``` - Check if we can still access the server: ```bash curl $IP ``` <!-- ```wait curl``` ```key ^C``` --> ] The `curl` command should now time out. .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Looking at the network policy This is the file that we applied: ```yaml kind: NetworkPolicy apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: deny-all-for-testweb spec: podSelector: matchLabels: app: testweb ingress: [] ``` .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Allowing connections only from specific pods - We want to allow traffic from pods with the label `run=testcurl` - Reminder: this label is automatically applied when we do `kubectl run testcurl ...` .exercise[ - Apply another policy: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/netpol-allow-testcurl-for-testweb.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Looking at the network policy This is the second file that we applied: ```yaml kind: NetworkPolicy apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: allow-testcurl-for-testweb spec: podSelector: matchLabels: app: testweb ingress: - from: - podSelector: matchLabels: run: testcurl ``` .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Testing the network policy - Let's create pods with, and without, the required label .exercise[ - Try to connect to testweb from a pod with the `run=testcurl` label: ```bash kubectl run testcurl --rm -i --image=centos -- curl -m3 $IP ``` - Try to connect to testweb with a different label: ```bash kubectl run testkurl --rm -i --image=centos -- curl -m3 $IP ``` ] The first command will work (and show the "Welcome to nginx!" page). The second command will fail and time out after 3 seconds. (The timeout is obtained with the `-m3` option.) .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## An important warning - Some network plugins only have partial support for network policies - For instance, Weave added support for egress rules [in version 2.4](https://github.com/weaveworks/weave/pull/3313) (released in July 2018) - But only recently added support for ipBlock [in version 2.5](https://github.com/weaveworks/weave/pull/3367) (released in Nov 2018) - Unsupported features might be silently ignored (Making you believe that you are secure, when you're not) .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Network policies, pods, and services - Network policies apply to *pods* - A *service* can select multiple pods (And load balance traffic across them) - It is possible that we can connect to some pods, but not some others (Because of how network policies have been defined for these pods) - In that case, connections to the service will randomly pass or fail (Depending on whether the connection was sent to a pod that we have access to or not) .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Network policies and namespaces - A good strategy is to isolate a namespace, so that: - all the pods in the namespace can communicate together - other namespaces cannot access the pods - external access has to be enabled explicitly - Let's see what this would look like for the DockerCoins app! .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Network policies for DockerCoins - We are going to apply two policies - The first policy will prevent traffic from other namespaces - The second policy will allow traffic to the `webui` pods - That's all we need for that app! .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Blocking traffic from other namespaces This policy selects all pods in the current namespace. It allows traffic only from pods in the current namespace. (An empty `podSelector` means "all pods.") ```yaml kind: NetworkPolicy apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: deny-from-other-namespaces spec: podSelector: {} ingress: - from: - podSelector: {} ``` .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Allowing traffic to `webui` pods This policy selects all pods with label `app=webui`. It allows traffic from any source. (An empty `from` field means "all sources.") ```yaml kind: NetworkPolicy apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1 metadata: name: allow-webui spec: podSelector: matchLabels: app: webui ingress: - from: [] ``` .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Applying both network policies - Both network policies are declared in the file `k8s/netpol-dockercoins.yaml` .exercise[ - Apply the network policies: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/netpol-dockercoins.yaml ``` - Check that we can still access the web UI from outside <br/> (and that the app is still working correctly!) - Check that we can't connect anymore to `rng` or `hasher` through their ClusterIP ] Note: using `kubectl proxy` or `kubectl port-forward` allows us to connect regardless of existing network policies. This allows us to debug and troubleshoot easily, without having to poke holes in our firewall. .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Cleaning up our network policies - The network policies that we have installed block all traffic to the default namespace - We should remove them, otherwise further exercises will fail! .exercise[ - Remove all network policies: ```bash kubectl delete networkpolicies --all ``` ] .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Protecting the control plane - Should we add network policies to block unauthorized access to the control plane? (etcd, API server, etc.) -- - At first, it seems like a good idea ... -- - But it *shouldn't* be necessary: - not all network plugins support network policies - the control plane is secured by other methods (mutual TLS, mostly) - the code running in our pods can reasonably expect to contact the API <br/> (and it can do so safely thanks to the API permission model) - If we block access to the control plane, we might disrupt legitimate code - ...Without necessarily improving security .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- ## Further resources - As always, the [Kubernetes documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/services-networking/network-policies/) is a good starting point - The API documentation has a lot of detail about the format of various objects: - [NetworkPolicy](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/generated/kubernetes-api/v1.12/#networkpolicy-v1-networking-k8s-io) - [NetworkPolicySpec](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/generated/kubernetes-api/v1.12/#networkpolicyspec-v1-networking-k8s-io) - [NetworkPolicyIngressRule](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/generated/kubernetes-api/v1.12/#networkpolicyingressrule-v1-networking-k8s-io) - etc. - And two resources by [Ahmet Alp Balkan](https://ahmet.im/): - a [very good talk about network policies](https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLj6h78yzYM2P-3-xqvmWaZbbI1sW-ulZb&v=3gGpMmYeEO8) at KubeCon North America 2017 - a repository of [ready-to-use recipes](https://github.com/ahmetb/kubernetes-network-policy-recipes) for network policies .debug[[k8s/netpol.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/netpol.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-authentication-and-authorization class: title Authentication and authorization .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-network-policies) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-1) | [Next section](#toc-stateful-sets) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Authentication and authorization *And first, a little refresher!* - Authentication = verifying the identity of a person On a UNIX system, we can authenticate with login+password, SSH keys ... - Authorization = listing what they are allowed to do On a UNIX system, this can include file permissions, sudoer entries ... - Sometimes abbreviated as "authn" and "authz" - In good modular systems, these things are decoupled (so we can e.g. change a password or SSH key without having to reset access rights) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication in Kubernetes - When the API server receives a request, it tries to authenticate it (it examines headers, certificates... anything available) - Many authentication methods are available and can be used simultaneously (we will see them on the next slide) - It's the job of the authentication method to produce: - the user name - the user ID - a list of groups - The API server doesn't interpret these; that'll be the job of *authorizers* .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication methods - TLS client certificates (that's what we've been doing with `kubectl` so far) - Bearer tokens (a secret token in the HTTP headers of the request) - [HTTP basic auth](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_access_authentication) (carrying user and password in an HTTP header) - Authentication proxy (sitting in front of the API and setting trusted headers) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Anonymous requests - If any authentication method *rejects* a request, it's denied (`401 Unauthorized` HTTP code) - If a request is neither rejected nor accepted by anyone, it's anonymous - the user name is `system:anonymous` - the list of groups is `[system:unauthenticated]` - By default, the anonymous user can't do anything (that's what you get if you just `curl` the Kubernetes API) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication with TLS certificates - This is enabled in most Kubernetes deployments - The user name is derived from the `CN` in the client certificates - The groups are derived from the `O` fields in the client certificate - From the point of view of the Kubernetes API, users do not exist (i.e. they are not stored in etcd or anywhere else) - Users can be created (and added to groups) independently of the API - The Kubernetes API can be set up to use your custom CA to validate client certs .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Viewing our admin certificate - Let's inspect the certificate we've been using all this time! .exercise[ - This command will show the `CN` and `O` fields for our certificate: ```bash kubectl config view \ --raw \ -o json \ | jq -r .users[0].user[\"client-certificate-data\"] \ | openssl base64 -d -A \ | openssl x509 -text \ | grep Subject: ``` ] Let's break down that command together! 😅 .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Breaking down the command - `kubectl config view` shows the Kubernetes user configuration - `--raw` includes certificate information (which shows as REDACTED otherwise) - `-o json` outputs the information in JSON format - `| jq ...` extracts the field with the user certificate (in base64) - `| openssl base64 -d -A` decodes the base64 format (now we have a PEM file) - `| openssl x509 -text` parses the certificate and outputs it as plain text - `| grep Subject:` shows us the line that interests us → We are user `kubernetes-admin`, in group `system:masters`. (We will see later how and why this gives us the permissions that we have.) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## User certificates in practice - The Kubernetes API server does not support certificate revocation (see issue [#18982](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/issues/18982)) - As a result, we don't have an easy way to terminate someone's access (if their key is compromised, or they leave the organization) - Option 1: re-create a new CA and re-issue everyone's certificates <br/> → Maybe OK if we only have a few users; no way otherwise - Option 2: don't use groups; grant permissions to individual users <br/> → Inconvenient if we have many users and teams; error-prone - Option 3: issue short-lived certificates (e.g. 24 hours) and renew them often <br/> → This can be facilitated by e.g. Vault or by the Kubernetes CSR API .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authentication with tokens - Tokens are passed as HTTP headers: `Authorization: Bearer and-then-here-comes-the-token` - Tokens can be validated through a number of different methods: - static tokens hard-coded in a file on the API server - [bootstrap tokens](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/bootstrap-tokens/) (special case to create a cluster or join nodes) - [OpenID Connect tokens](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authentication/#openid-connect-tokens) (to delegate authentication to compatible OAuth2 providers) - service accounts (these deserve more details, coming right up!) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Service accounts - A service account is a user that exists in the Kubernetes API (it is visible with e.g. `kubectl get serviceaccounts`) - Service accounts can therefore be created / updated dynamically (they don't require hand-editing a file and restarting the API server) - A service account is associated with a set of secrets (the kind that you can view with `kubectl get secrets`) - Service accounts are generally used to grant permissions to applications, services... (as opposed to humans) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Token authentication in practice - We are going to list existing service accounts - Then we will extract the token for a given service account - And we will use that token to authenticate with the API .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Listing service accounts .exercise[ - The resource name is `serviceaccount` or `sa` for short: ```bash kubectl get sa ``` ] There should be just one service account in the default namespace: `default`. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Finding the secret .exercise[ - List the secrets for the `default` service account: ```bash kubectl get sa default -o yaml SECRET=$(kubectl get sa default -o json | jq -r .secrets[0].name) ``` ] It should be named `default-token-XXXXX`. .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Extracting the token - The token is stored in the secret, wrapped with base64 encoding .exercise[ - View the secret: ```bash kubectl get secret $SECRET -o yaml ``` - Extract the token and decode it: ```bash TOKEN=$(kubectl get secret $SECRET -o json \ | jq -r .data.token | openssl base64 -d -A) ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Using the token - Let's send a request to the API, without and with the token .exercise[ - Find the ClusterIP for the `kubernetes` service: ```bash kubectl get svc kubernetes API=$(kubectl get svc kubernetes -o json | jq -r .spec.clusterIP) ``` - Connect without the token: ```bash curl -k https://$API ``` - Connect with the token: ```bash curl -k -H "Authorization: Bearer $TOKEN" https://$API ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Results - In both cases, we will get a "Forbidden" error - Without authentication, the user is `system:anonymous` - With authentication, it is shown as `system:serviceaccount:default:default` - The API "sees" us as a different user - But neither user has any rights, so we can't do nothin' - Let's change that! .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Authorization in Kubernetes - There are multiple ways to grant permissions in Kubernetes, called [authorizers](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authorization/#authorization-modules): - [Node Authorization](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/node/) (used internally by kubelet; we can ignore it) - [Attribute-based access control](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/abac/) (powerful but complex and static; ignore it too) - [Webhook](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/webhook/) (each API request is submitted to an external service for approval) - [Role-based access control](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/) (associates permissions to users dynamically) - The one we want is the last one, generally abbreviated as RBAC .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Role-based access control - RBAC allows to specify fine-grained permissions - Permissions are expressed as *rules* - A rule is a combination of: - [verbs](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/authorization/#determine-the-request-verb) like create, get, list, update, delete... - resources (as in "API resource," like pods, nodes, services...) - resource names (to specify e.g. one specific pod instead of all pods) - in some case, [subresources](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/#referring-to-resources) (e.g. logs are subresources of pods) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## From rules to roles to rolebindings - A *role* is an API object containing a list of *rules* Example: role "external-load-balancer-configurator" can: - [list, get] resources [endpoints, services, pods] - [update] resources [services] - A *rolebinding* associates a role with a user Example: rolebinding "external-load-balancer-configurator": - associates user "external-load-balancer-configurator" - with role "external-load-balancer-configurator" - Yes, there can be users, roles, and rolebindings with the same name - It's a good idea for 1-1-1 bindings; not so much for 1-N ones .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Cluster-scope permissions - API resources Role and RoleBinding are for objects within a namespace - We can also define API resources ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding - These are a superset, allowing us to: - specify actions on cluster-wide objects (like nodes) - operate across all namespaces - We can create Role and RoleBinding resources within a namespace - ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding resources are global .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Pods and service accounts - A pod can be associated with a service account - by default, it is associated with the `default` service account - as we saw earlier, this service account has no permissions anyway - The associated token is exposed to the pod's filesystem (in `/var/run/secrets/kubernetes.io/serviceaccount/token`) - Standard Kubernetes tooling (like `kubectl`) will look for it there - So Kubernetes tools running in a pod will automatically use the service account .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## In practice - We are going to create a service account - We will use a default cluster role (`view`) - We will bind together this role and this service account - Then we will run a pod using that service account - In this pod, we will install `kubectl` and check our permissions .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Creating a service account - We will call the new service account `viewer` (note that nothing prevents us from calling it `view`, like the role) .exercise[ - Create the new service account: ```bash kubectl create serviceaccount viewer ``` - List service accounts now: ```bash kubectl get serviceaccounts ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Binding a role to the service account - Binding a role = creating a *rolebinding* object - We will call that object `viewercanview` (but again, we could call it `view`) .exercise[ - Create the new role binding: ```bash kubectl create rolebinding viewercanview \ --clusterrole=view \ --serviceaccount=default:viewer ``` ] It's important to note a couple of details in these flags... .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Roles vs Cluster Roles - We used `--clusterrole=view` - What would have happened if we had used `--role=view`? - we would have bound the role `view` from the local namespace <br/>(instead of the cluster role `view`) - the command would have worked fine (no error) - but later, our API requests would have been denied - This is a deliberate design decision (we can reference roles that don't exist, and create/update them later) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Users vs Service Accounts - We used `--serviceaccount=default:viewer` - What would have happened if we had used `--user=default:viewer`? - we would have bound the role to a user instead of a service account - again, the command would have worked fine (no error) - ...but our API requests would have been denied later - What's about the `default:` prefix? - that's the namespace of the service account - yes, it could be inferred from context, but... `kubectl` requires it .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Testing - We will run an `alpine` pod and install `kubectl` there .exercise[ - Run a one-time pod: ```bash kubectl run eyepod --rm -ti --restart=Never \ --serviceaccount=viewer \ --image alpine ``` - Install `curl`, then use it to install `kubectl`: ```bash apk add --no-cache curl URLBASE=https://storage.googleapis.com/kubernetes-release/release KUBEVER=$(curl -s $URLBASE/stable.txt) curl -LO $URLBASE/$KUBEVER/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl chmod +x kubectl ``` ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Running `kubectl` in the pod - We'll try to use our `view` permissions, then to create an object .exercise[ - Check that we can, indeed, view things: ```bash ./kubectl get all ``` - But that we can't create things: ``` ./kubectl create deployment testrbac --image=nginx ``` - Exit the container with `exit` or `^D` <!-- ```key ^D``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- ## Testing directly with `kubectl` - We can also check for permission with `kubectl auth can-i`: ```bash kubectl auth can-i list nodes kubectl auth can-i create pods kubectl auth can-i get pod/name-of-pod kubectl auth can-i get /url-fragment-of-api-request/ kubectl auth can-i '*' services ``` - And we can check permissions on behalf of other users: ```bash kubectl auth can-i list nodes \ --as some-user kubectl auth can-i list nodes \ --as system:serviceaccount:<namespace>:<name-of-service-account> ``` .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Where does this `view` role come from? - Kubernetes defines a number of ClusterRoles intended to be bound to users - `cluster-admin` can do *everything* (think `root` on UNIX) - `admin` can do *almost everything* (except e.g. changing resource quotas and limits) - `edit` is similar to `admin`, but cannot view or edit permissions - `view` has read-only access to most resources, except permissions and secrets *In many situations, these roles will be all you need.* *You can also customize them!* .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Customizing the default roles - If you need to *add* permissions to these default roles (or others), <br/> you can do it through the [ClusterRole Aggregation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac/#aggregated-clusterroles) mechanism - This happens by creating a ClusterRole with the following labels: ```yaml metadata: labels: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-admin: "true" rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-edit: "true" rbac.authorization.k8s.io/aggregate-to-view: "true" ``` - This ClusterRole permissions will be added to `admin`/`edit`/`view` respectively - This is particulary useful when using CustomResourceDefinitions (since Kubernetes cannot guess which resources are sensitive and which ones aren't) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Where do our permissions come from? - When interacting with the Kubernetes API, we are using a client certificate - We saw previously that this client certificate contained: `CN=kubernetes-admin` and `O=system:masters` - Let's look for these in existing ClusterRoleBindings: ```bash kubectl get clusterrolebindings -o yaml | grep -e kubernetes-admin -e system:masters ``` (`system:masters` should show up, but not `kubernetes-admin`.) - Where does this match come from? .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## The `system:masters` group - If we eyeball the output of `kubectl get clusterrolebindings -o yaml`, we'll find out! - It is in the `cluster-admin` binding: ```bash kubectl describe clusterrolebinding cluster-admin ``` - This binding associates `system:masters` with the cluster role `cluster-admin` - And the `cluster-admin` is, basically, `root`: ```bash kubectl describe clusterrole cluster-admin ``` .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Figuring out who can do what - For auditing purposes, sometimes we want to know who can perform an action - There are a few tools to help us with that - [kubectl-who-can](https://github.com/aquasecurity/kubectl-who-can) by Aqua Security - [Review Access (aka Rakkess)](https://github.com/corneliusweig/rakkess) - Both are available as standalone programs, or as plugins for `kubectl` (`kubectl` plugins can be installed and managed with `krew`) .debug[[k8s/authn-authz.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/authn-authz.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-stateful-sets class: title Stateful sets .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-authentication-and-authorization) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-2) | [Next section](#toc-running-a-consul-cluster) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Stateful sets - Stateful sets are a type of resource in the Kubernetes API (like pods, deployments, services...) - They offer mechanisms to deploy scaled stateful applications - At a first glance, they look like *deployments*: - a stateful set defines a pod spec and a number of replicas *R* - it will make sure that *R* copies of the pod are running - that number can be changed while the stateful set is running - updating the pod spec will cause a rolling update to happen - But they also have some significant differences .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Stateful sets unique features - Pods in a stateful set are numbered (from 0 to *R-1*) and ordered - They are started and updated in order (from 0 to *R-1*) - A pod is started (or updated) only when the previous one is ready - They are stopped in reverse order (from *R-1* to 0) - Each pod know its identity (i.e. which number it is in the set) - Each pod can discover the IP address of the others easily - The pods can persist data on attached volumes 🤔 Wait a minute ... Can't we already attach volumes to pods and deployments? .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Revisiting volumes - [Volumes](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/storage/volumes/) are used for many purposes: - sharing data between containers in a pod - exposing configuration information and secrets to containers - accessing storage systems - Let's see examples of the latter usage .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Volumes types - There are many [types of volumes](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/storage/volumes/#types-of-volumes) available: - public cloud storage (GCEPersistentDisk, AWSElasticBlockStore, AzureDisk...) - private cloud storage (Cinder, VsphereVolume...) - traditional storage systems (NFS, iSCSI, FC...) - distributed storage (Ceph, Glusterfs, Portworx...) - Using a persistent volume requires: - creating the volume out-of-band (outside of the Kubernetes API) - referencing the volume in the pod description, with all its parameters .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Using a cloud volume Here is a pod definition using an AWS EBS volume (that has to be created first): ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: pod-using-my-ebs-volume spec: containers: - image: ... name: container-using-my-ebs-volume volumeMounts: - mountPath: /my-ebs name: my-ebs-volume volumes: - name: my-ebs-volume awsElasticBlockStore: volumeID: vol-049df61146c4d7901 fsType: ext4 ``` .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Using an NFS volume Here is another example using a volume on an NFS server: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: pod-using-my-nfs-volume spec: containers: - image: ... name: container-using-my-nfs-volume volumeMounts: - mountPath: /my-nfs name: my-nfs-volume volumes: - name: my-nfs-volume nfs: server: 192.168.0.55 path: "/exports/assets" ``` .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Shortcomings of volumes - Their lifecycle (creation, deletion...) is managed outside of the Kubernetes API (we can't just use `kubectl apply/create/delete/...` to manage them) - If a Deployment uses a volume, all replicas end up using the same volume - That volume must then support concurrent access - some volumes do (e.g. NFS servers support multiple read/write access) - some volumes support concurrent reads - some volumes support concurrent access for colocated pods - What we really need is a way for each replica to have its own volume .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Persistent Volume Claims - To abstract the different types of storage, a pod can use a special volume type - This type is a *Persistent Volume Claim* - A Persistent Volume Claim (PVC) is a resource type (visible with `kubectl get persistentvolumeclaims` or `kubectl get pvc`) - A PVC is not a volume; it is a *request for a volume* .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Persistent Volume Claims in practice - Using a Persistent Volume Claim is a two-step process: - creating the claim - using the claim in a pod (as if it were any other kind of volume) - A PVC starts by being Unbound (without an associated volume) - Once it is associated with a Persistent Volume, it becomes Bound - A Pod referring an unbound PVC will not start (but as soon as the PVC is bound, the Pod can start) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Binding PV and PVC - A Kubernetes controller continuously watches PV and PVC objects - When it notices an unbound PVC, it tries to find a satisfactory PV ("satisfactory" in terms of size and other characteristics; see next slide) - If no PV fits the PVC, a PV can be created dynamically (this requires to configure a *dynamic provisioner*, more on that later) - Otherwise, the PVC remains unbound indefinitely (until we manually create a PV or setup dynamic provisioning) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## What's in a Persistent Volume Claim? - At the very least, the claim should indicate: - the size of the volume (e.g. "5 GiB") - the access mode (e.g. "read-write by a single pod") - Optionally, it can also specify a Storage Class - The Storage Class indicates: - which storage system to use (e.g. Portworx, EBS...) - extra parameters for that storage system e.g.: "replicate the data 3 times, and use SSD media" .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## What's a Storage Class? - A Storage Class is yet another Kubernetes API resource (visible with e.g. `kubectl get storageclass` or `kubectl get sc`) - It indicates which *provisioner* to use (which controller will create the actual volume) - And arbitrary parameters for that provisioner (replication levels, type of disk ... anything relevant!) - Storage Classes are required if we want to use [dynamic provisioning](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/storage/dynamic-provisioning/) (but we can also create volumes manually, and ignore Storage Classes) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Defining a Persistent Volume Claim Here is a minimal PVC: ```yaml kind: PersistentVolumeClaim apiVersion: v1 metadata: name: my-claim spec: accessModes: - ReadWriteOnce resources: requests: storage: 1Gi ``` .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Using a Persistent Volume Claim Here is a Pod definition like the ones shown earlier, but using a PVC: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: Pod metadata: name: pod-using-a-claim spec: containers: - image: ... name: container-using-a-claim volumeMounts: - mountPath: /my-vol name: my-volume volumes: - name: my-volume persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: my-claim ``` .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Persistent Volume Claims and Stateful sets - The pods in a stateful set can define a `volumeClaimTemplate` - A `volumeClaimTemplate` will dynamically create one Persistent Volume Claim per pod - Each pod will therefore have its own volume - These volumes are numbered (like the pods) - When updating the stateful set (e.g. image upgrade), each pod keeps its volume - When pods get rescheduled (e.g. node failure), they keep their volume (this requires a storage system that is not node-local) - These volumes are not automatically deleted (when the stateful set is scaled down or deleted) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Stateful set recap - A Stateful sets manages a number of identical pods (like a Deployment) - These pods are numbered, and started/upgraded/stopped in a specific order - These pods are aware of their number (e.g., #0 can decide to be the primary, and #1 can be secondary) - These pods can find the IP addresses of the other pods in the set (through a *headless service*) - These pods can each have their own persistent storage (Deployments cannot do that) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-running-a-consul-cluster class: title Running a Consul cluster .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-stateful-sets) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-2) | [Next section](#toc-local-persistent-volumes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Running a Consul cluster - Here is a good use-case for Stateful sets! - We are going to deploy a Consul cluster with 3 nodes - Consul is a highly-available key/value store (like etcd or Zookeeper) - One easy way to bootstrap a cluster is to tell each node: - the addresses of other nodes - how many nodes are expected (to know when quorum is reached) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Bootstrapping a Consul cluster *After reading the Consul documentation carefully (and/or asking around), we figure out the minimal command-line to run our Consul cluster.* ``` consul agent -data-dir=/consul/data -client=0.0.0.0 -server -ui \ -bootstrap-expect=3 \ -retry-join=`X.X.X.X` \ -retry-join=`Y.Y.Y.Y` ``` - Replace X.X.X.X and Y.Y.Y.Y with the addresses of other nodes - The same command-line can be used on all nodes (convenient!) .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Cloud Auto-join - Since version 1.4.0, Consul can use the Kubernetes API to find its peers - This is called [Cloud Auto-join] - Instead of passing an IP address, we need to pass a parameter like this: ``` consul agent -retry-join "provider=k8s label_selector=\"app=consul\"" ``` - Consul needs to be able to talk to the Kubernetes API - We can provide a `kubeconfig` file - If Consul runs in a pod, it will use the *service account* of the pod [Cloud Auto-join]: https://www.consul.io/docs/agent/cloud-auto-join.html#kubernetes-k8s- .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Setting up Cloud auto-join - We need to create a service account for Consul - We need to create a role that can `list` and `get` pods - We need to bind that role to the service account - And of course, we need to make sure that Consul pods use that service account .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Putting it all together - The file `k8s/consul.yaml` defines the required resources (service account, cluster role, cluster role binding, service, stateful set) - It has a few extra touches: - a `podAntiAffinity` prevents two pods from running on the same node - a `preStop` hook makes the pod leave the cluster when shutdown gracefully This was inspired by this [excellent tutorial](https://github.com/kelseyhightower/consul-on-kubernetes) by Kelsey Hightower. Some features from the original tutorial (TLS authentication between nodes and encryption of gossip traffic) were removed for simplicity. .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Running our Consul cluster - We'll use the provided YAML file .exercise[ - Create the stateful set and associated service: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/consul.yaml ``` - Check the logs as the pods come up one after another: ```bash stern consul ``` <!-- ```wait Synced node info``` ```key ^C``` --> - Check the health of the cluster: ```bash kubectl exec consul-0 consul members ``` ] .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Caveats - We haven't used a `volumeClaimTemplate` here - That's because we don't have a storage provider yet (except if you're running this on your own and your cluster has one) - What happens if we lose a pod? - a new pod gets rescheduled (with an empty state) - the new pod tries to connect to the two others - it will be accepted (after 1-2 minutes of instability) - and it will retrieve the data from the other pods .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- ## Failure modes - What happens if we lose two pods? - manual repair will be required - we will need to instruct the remaining one to act solo - then rejoin new pods - What happens if we lose three pods? (aka all of them) - we lose all the data (ouch) - If we run Consul without persistent storage, backups are a good idea! .debug[[k8s/statefulsets.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/statefulsets.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-local-persistent-volumes class: title Local Persistent Volumes .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-running-a-consul-cluster) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-2) | [Next section](#toc-highly-available-persistent-volumes) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Local Persistent Volumes - We want to run that Consul cluster *and* actually persist data - But we don't have a distributed storage system - We are going to use local volumes instead (similar conceptually to `hostPath` volumes) - We can use local volumes without installing extra plugins - However, they are tied to a node - If that node goes down, the volume becomes unavailable .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## With or without dynamic provisioning - We will deploy a Consul cluster *with* persistence - That cluster's StatefulSet will create PVCs - These PVCs will remain unbound¹, until we will create local volumes manually (we will basically do the job of the dynamic provisioner) - Then, we will see how to automate that with a dynamic provisioner .footnote[¹Unbound = without an associated Persistent Volume.] .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## If we have a dynamic provisioner ... - The labs in this section assume that we *do not* have a dynamic provisioner - If we do have one, we need to disable it .exercise[ - Check if we have a dynamic provisioner: ```bash kubectl get storageclass ``` - If the output contains a line with `(default)`, run this command: ```bash kubectl annotate sc storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class- --all ``` - Check again that it is no longer marked as `(default)` ] .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Deploying Consul - We will use a slightly different YAML file - The only differences between that file and the previous one are: - `volumeClaimTemplate` defined in the Stateful Set spec - the corresponding `volumeMounts` in the Pod spec - the label `consul` has been changed to `persistentconsul` <br/> (to avoid conflicts with the other Stateful Set) .exercise[ - Apply the persistent Consul YAML file: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/persistent-consul.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Observing the situation - Let's look at Persistent Volume Claims and Pods .exercise[ - Check that we now have an unbound Persistent Volume Claim: ```bash kubectl get pvc ``` - We don't have any Persistent Volume: ```bash kubectl get pv ``` - The Pod `persistentconsul-0` is not scheduled yet: ```bash kubectl get pods -o wide ``` ] *Hint: leave these commands running with `-w` in different windows.* .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Explanations - In a Stateful Set, the Pods are started one by one - `persistentconsul-1` won't be created until `persistentconsul-0` is running - `persistentconsul-0` has a dependency on an unbound Persistent Volume Claim - The scheduler won't schedule the Pod until the PVC is bound (because the PVC might be bound to a volume that is only available on a subset of nodes; for instance EBS are tied to an availability zone) .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Creating Persistent Volumes - Let's create 3 local directories (`/mnt/consul`) on node2, node3, node4 - Then create 3 Persistent Volumes corresponding to these directories .exercise[ - Create the local directories: ```bash for NODE in node2 node3 node4; do ssh $NODE sudo mkdir -p /mnt/consul done ``` - Create the PV objects: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/volumes-for-consul.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Check our Consul cluster - The PVs that we created will be automatically matched with the PVCs - Once a PVC is bound, its pod can start normally - Once the pod `persistentconsul-0` has started, `persistentconsul-1` can be created, etc. - Eventually, our Consul cluster is up, and backend by "persistent" volumes .exercise[ - Check that our Consul clusters has 3 members indeed: ```bash kubectl exec persistentconsul-0 consul members ``` ] .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Devil is in the details (1/2) - The size of the Persistent Volumes is bogus (it is used when matching PVs and PVCs together, but there is no actual quota or limit) .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Devil is in the details (2/2) - This specific example worked because we had exactly 1 free PV per node: - if we had created multiple PVs per node ... - we could have ended with two PVCs bound to PVs on the same node ... - which would have required two pods to be on the same node ... - which is forbidden by the anti-affinity constraints in the StatefulSet - To avoid that, we need to associated the PVs with a Storage Class that has: ```yaml volumeBindingMode: WaitForFirstConsumer ``` (this means that a PVC will be bound to a PV only after being used by a Pod) - See [this blog post](https://kubernetes.io/blog/2018/04/13/local-persistent-volumes-beta/) for more details .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Bulk provisioning - It's not practical to manually create directories and PVs for each app - We *could* pre-provision a number of PVs across our fleet - We could even automate that with a Daemon Set: - creating a number of directories on each node - creating the corresponding PV objects - We also need to recycle volumes - ... This can quickly get out of hand .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Dynamic provisioning - We could also write our own provisioner, which would: - watch the PVCs across all namespaces - when a PVC is created, create a corresponding PV on a node - Or we could use one of the dynamic provisioners for local persistent volumes (for instance the [Rancher local path provisioner](https://github.com/rancher/local-path-provisioner)) .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- ## Strategies for local persistent volumes - Remember, when a node goes down, the volumes on that node become unavailable - High availability will require another layer of replication (like what we've just seen with Consul; or primary/secondary; etc) - Pre-provisioning PVs makes sense for machines with local storage (e.g. cloud instance storage; or storage directly attached to a physical machine) - Dynamic provisioning makes sense for large number of applications (when we can't or won't dedicate a whole disk to a volume) - It's possible to mix both (using distinct Storage Classes) .debug[[k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/local-persistent-volumes.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-highly-available-persistent-volumes class: title Highly available Persistent Volumes .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-local-persistent-volumes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-2) | [Next section](#toc-resource-limits) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Highly available Persistent Volumes - How can we achieve true durability? - How can we store data that would survive the loss of a node? -- - We need to use Persistent Volumes backed by highly available storage systems - There are many ways to achieve that: - leveraging our cloud's storage APIs - using NAS/SAN systems or file servers - distributed storage systems -- - We are going to see one distributed storage system in action .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Our test scenario - We will set up a distributed storage system on our cluster - We will use it to deploy a SQL database (PostgreSQL) - We will insert some test data in the database - We will disrupt the node running the database - We will see how it recovers .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Portworx - Portworx is a *commercial* persistent storage solution for containers - It works with Kubernetes, but also Mesos, Swarm ... - It provides [hyper-converged](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyper-converged_infrastructure) storage (=storage is provided by regular compute nodes) - We're going to use it here because it can be deployed on any Kubernetes cluster (it doesn't require any particular infrastructure) - We don't endorse or support Portworx in any particular way (but we appreciate that it's super easy to install!) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## A useful reminder - We're installing Portworx because we need a storage system - If you are using AKS, EKS, GKE ... you already have a storage system (but you might want another one, e.g. to leverage local storage) - If you have setup Kubernetes yourself, there are other solutions available too - on premises, you can use a good old SAN/NAS - on a private cloud like OpenStack, you can use e.g. Cinder - everywhere, you can use other systems, e.g. Gluster, StorageOS .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Portworx requirements - Kubernetes cluster ✔️ - Optional key/value store (etcd or Consul) ❌ - At least one available block device ❌ .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## The key-value store - In the current version of Portworx (1.4) it is recommended to use etcd or Consul - But Portworx also has beta support for an embedded key/value store - For simplicity, we are going to use the latter option (but if we have deployed Consul or etcd, we can use that, too) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## One available block device - Block device = disk or partition on a disk - We can see block devices with `lsblk` (or `cat /proc/partitions` if we're old school like that!) - If we don't have a spare disk or partition, we can use a *loop device* - A loop device is a block device actually backed by a file - These are frequently used to mount ISO (CD/DVD) images or VM disk images .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Setting up a loop device - We are going to create a 10 GB (empty) file on each node - Then make a loop device from it, to be used by Portworx .exercise[ - Create a 10 GB file on each node: ```bash for N in $(seq 1 4); do ssh node$N sudo truncate --size 10G /portworx.blk; done ``` (If SSH asks to confirm host keys, enter `yes` each time.) - Associate the file to a loop device on each node: ```bash for N in $(seq 1 4); do ssh node$N sudo losetup /dev/loop4 /portworx.blk; done ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Installing Portworx - To install Portworx, we need to go to https://install.portworx.com/ - This website will ask us a bunch of questions about our cluster - Then, it will generate a YAML file that we should apply to our cluster -- - Or, we can just apply that YAML file directly (it's in `k8s/portworx.yaml`) .exercise[ - Install Portworx: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/portworx.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Generating a custom YAML file If you want to generate a YAML file tailored to your own needs, the easiest way is to use https://install.portworx.com/. FYI, this is how we obtained the YAML file used earlier: ``` KBVER=$(kubectl version -o json | jq -r .serverVersion.gitVersion) BLKDEV=/dev/loop4 curl https://install.portworx.com/1.4/?kbver=$KBVER&b=true&s=$BLKDEV&c=px-workshop&stork=true&lh=true ``` If you want to use an external key/value store, add one of the following: ``` &k=etcd://`XXX`:2379 &k=consul://`XXX`:8500 ``` ... where `XXX` is the name or address of your etcd or Consul server. .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Waiting for Portworx to be ready - The installation process will take a few minutes .exercise[ - Check out the logs: ```bash stern -n kube-system portworx ``` - Wait until it gets quiet (you should see `portworx service is healthy`, too) <!-- ```longwait PX node status reports portworx service is healthy``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Dynamic provisioning of persistent volumes - We are going to run PostgreSQL in a Stateful set - The Stateful set will specify a `volumeClaimTemplate` - That `volumeClaimTemplate` will create Persistent Volume Claims - Kubernetes' [dynamic provisioning](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/storage/dynamic-provisioning/) will satisfy these Persistent Volume Claims (by creating Persistent Volumes and binding them to the claims) - The Persistent Volumes are then available for the PostgreSQL pods .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Storage Classes - It's possible that multiple storage systems are available - Or, that a storage system offers multiple tiers of storage (SSD vs. magnetic; mirrored or not; etc.) - We need to tell Kubernetes *which* system and tier to use - This is achieved by creating a Storage Class - A `volumeClaimTemplate` can indicate which Storage Class to use - It is also possible to mark a Storage Class as "default" (it will be used if a `volumeClaimTemplate` doesn't specify one) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Check our default Storage Class - The YAML manifest applied earlier should define a default storage class .exercise[ - Check that we have a default storage class: ```bash kubectl get storageclass ``` ] There should be a storage class showing as `portworx-replicated (default)`. .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Our default Storage Class This is our Storage Class (in `k8s/storage-class.yaml`): ```yaml kind: StorageClass apiVersion: storage.k8s.io/v1beta1 metadata: name: portworx-replicated annotations: storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class: "true" provisioner: kubernetes.io/portworx-volume parameters: repl: "2" priority_io: "high" ``` - It says "use Portworx to create volumes" - It tells Portworx to "keep 2 replicas of these volumes" - It marks the Storage Class as being the default one .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Our Postgres Stateful set - The next slide shows `k8s/postgres.yaml` - It defines a Stateful set - With a `volumeClaimTemplate` requesting a 1 GB volume - That volume will be mounted to `/var/lib/postgresql/data` - There is another little detail: we enable the `stork` scheduler - The `stork` scheduler is optional (it's specific to Portworx) - It helps the Kubernetes scheduler to colocate the pod with its volume (see [this blog post](https://portworx.com/stork-storage-orchestration-kubernetes/) for more details about that) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- .small[ ```yaml apiVersion: apps/v1 kind: StatefulSet metadata: name: postgres spec: selector: matchLabels: app: postgres serviceName: postgres template: metadata: labels: app: postgres spec: schedulerName: stork containers: - name: postgres image: postgres:11 volumeMounts: - mountPath: /var/lib/postgresql/data name: postgres volumeClaimTemplates: - metadata: name: postgres spec: accessModes: ["ReadWriteOnce"] resources: requests: storage: 1Gi ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Creating the Stateful set - Before applying the YAML, watch what's going on with `kubectl get events -w` .exercise[ - Apply that YAML: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/postgres.yaml ``` <!-- ```hide kubectl wait pod postgres-0 --for condition=ready``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Testing our PostgreSQL pod - We will use `kubectl exec` to get a shell in the pod - Good to know: we need to use the `postgres` user in the pod .exercise[ - Get a shell in the pod, as the `postgres` user: ```bash kubectl exec -ti postgres-0 su postgres ``` <!-- autopilot prompt detection expects $ or # at the beginning of the line. ```wait postgres@postgres``` ```keys PS1="\u@\h:\w\n\$ "``` ```key ^J``` --> - Check that default databases have been created correctly: ```bash psql -l ``` ] (This should show us 3 lines: postgres, template0, and template1.) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Inserting data in PostgreSQL - We will create a database and populate it with `pgbench` .exercise[ - Create a database named `demo`: ```bash createdb demo ``` - Populate it with `pgbench`: ```bash pgbench -i -s 10 demo ``` ] - The `-i` flag means "create tables" - The `-s 10` flag means "create 10 x 100,000 rows" .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Checking how much data we have now - The `pgbench` tool inserts rows in table `pgbench_accounts` .exercise[ - Check that the `demo` base exists: ```bash psql -l ``` - Check how many rows we have in `pgbench_accounts`: ```bash psql demo -c "select count(*) from pgbench_accounts" ``` <!-- ```key ^D``` --> ] (We should see a count of 1,000,000 rows.) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Find out which node is hosting the database - We can find that information with `kubectl get pods -o wide` .exercise[ - Check the node running the database: ```bash kubectl get pod postgres-0 -o wide ``` ] We are going to disrupt that node. -- By "disrupt" we mean: "disconnect it from the network". .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Disconnect the node - We will use `iptables` to block all traffic exiting the node (except SSH traffic, so we can repair the node later if needed) .exercise[ - SSH to the node to disrupt: ```bash ssh `nodeX` ``` - Allow SSH traffic leaving the node, but block all other traffic: ```bash sudo iptables -I OUTPUT -p tcp --sport 22 -j ACCEPT sudo iptables -I OUTPUT 2 -j DROP ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Check that the node is disconnected .exercise[ - Check that the node can't communicate with other nodes: ``` ping node1 ``` - Logout to go back on `node1` <!-- ```key ^D``` --> - Watch the events unfolding with `kubectl get events -w` and `kubectl get pods -w` ] - It will take some time for Kubernetes to mark the node as unhealthy - Then it will attempt to reschedule the pod to another node - In about a minute, our pod should be up and running again .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Check that our data is still available - We are going to reconnect to the (new) pod and check .exercise[ - Get a shell on the pod: ```bash kubectl exec -ti postgres-0 su postgres ``` <!-- ```wait postgres@postgres``` ```keys PS1="\u@\h:\w\n\$ "``` ```key ^J``` --> - Check the number of rows in the `pgbench_accounts` table: ```bash psql demo -c "select count(*) from pgbench_accounts" ``` <!-- ```key ^D``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Double-check that the pod has really moved - Just to make sure the system is not bluffing! .exercise[ - Look at which node the pod is now running on ```bash kubectl get pod postgres-0 -o wide ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Re-enable the node - Let's fix the node that we disconnected from the network .exercise[ - SSH to the node: ```bash ssh `nodeX` ``` - Remove the iptables rule blocking traffic: ```bash sudo iptables -D OUTPUT 2 ``` ] .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## A few words about this PostgreSQL setup - In a real deployment, you would want to set a password - This can be done by creating a `secret`: ``` kubectl create secret generic postgres \ --from-literal=password=$(base64 /dev/urandom | head -c16) ``` - And then passing that secret to the container: ```yaml env: - name: POSTGRES_PASSWORD valueFrom: secretKeyRef: name: postgres key: password ``` .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Troubleshooting Portworx - If we need to see what's going on with Portworx: ``` PXPOD=$(kubectl -n kube-system get pod -l name=portworx -o json | jq -r .items[0].metadata.name) kubectl -n kube-system exec $PXPOD -- /opt/pwx/bin/pxctl status ``` - We can also connect to Lighthouse (a web UI) - check the port with `kubectl -n kube-system get svc px-lighthouse` - connect to that port - the default login/password is `admin/Password1` - then specify `portworx-service` as the endpoint .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Removing Portworx - Portworx provides a storage driver - It needs to place itself "above" the Kubelet (it installs itself straight on the nodes) - To remove it, we need to do more than just deleting its Kubernetes resources - It is done by applying a special label: ``` kubectl label nodes --all px/enabled=remove --overwrite ``` - Then removing a bunch of local files: ``` sudo chattr -i /etc/pwx/.private.json sudo rm -rf /etc/pwx /opt/pwx ``` (on each node where Portworx was running) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Dynamic provisioning without a provider - What if we want to use Stateful sets without a storage provider? - We will have to create volumes manually (by creating Persistent Volume objects) - These volumes will be automatically bound with matching Persistent Volume Claims - We can use local volumes (essentially bind mounts of host directories) - Of course, these volumes won't be available in case of node failure - Check [this blog post](https://kubernetes.io/blog/2018/04/13/local-persistent-volumes-beta/) for more information and gotchas .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- ## Acknowledgements The Portworx installation tutorial, and the PostgreSQL example, were inspired by [Portworx examples on Katacoda](https://katacoda.com/portworx/scenarios/), in particular: - [installing Portworx on Kubernetes](https://www.katacoda.com/portworx/scenarios/deploy-px-k8s) (with adapatations to use a loop device and an embedded key/value store) - [persistent volumes on Kubernetes using Portworx](https://www.katacoda.com/portworx/scenarios/px-k8s-vol-basic) (with adapatations to specify a default Storage Class) - [HA PostgreSQL on Kubernetes with Portworx](https://www.katacoda.com/portworx/scenarios/px-k8s-postgres-all-in-one) (with adaptations to use a Stateful Set and simplify PostgreSQL's setup) .debug[[k8s/portworx.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/portworx.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-resource-limits class: title Resource Limits .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-highly-available-persistent-volumes) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Resource Limits - We can attach resource indications to our pods (or rather: to the *containers* in our pods) - We can specify *limits* and/or *requests* - We can specify quantities of CPU and/or memory .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## CPU vs memory - CPU is a *compressible resource* (it can be preempted immediately without adverse effect) - Memory is an *incompressible resource* (it needs to be swapped out to be reclaimed; and this is costly) - As a result, exceeding limits will have different consequences for CPU and memory .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Exceeding CPU limits - CPU can be reclaimed instantaneously (in fact, it is preempted hundreds of times per second, at each context switch) - If a container uses too much CPU, it can be throttled (it will be scheduled less often) - The processes in that container will run slower (or rather: they will not run faster) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Exceeding memory limits - Memory needs to be swapped out before being reclaimed - "Swapping" means writing memory pages to disk, which is very slow - On a classic system, a process that swaps can get 1000x slower (because disk I/O is 1000x slower than memory I/O) - Exceeding the memory limit (even by a small amount) can reduce performance *a lot* - Kubernetes *does not support swap* (more on that later!) - Exceeding the memory limit will cause the container to be killed .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Limits vs requests - Limits are "hard limits" (they can't be exceeded) - a container exceeding its memory limit is killed - a container exceeding its CPU limit is throttled - Requests are used for scheduling purposes - a container using *less* than what it requested will never be killed or throttled - the scheduler uses the requested sizes to determine placement - the resources requested by all pods on a node will never exceed the node size .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Pod quality of service Each pod is assigned a QoS class (visible in `status.qosClass`). - If limits = requests: - as long as the container uses less than the limit, it won't be affected - if all containers in a pod have *(limits=requests)*, QoS is considered "Guaranteed" - If requests < limits: - as long as the container uses less than the request, it won't be affected - otherwise, it might be killed/evicted if the node gets overloaded - if at least one container has *(requests<limits)*, QoS is considered "Burstable" - If a pod doesn't have any request nor limit, QoS is considered "BestEffort" .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Quality of service impact - When a node is overloaded, BestEffort pods are killed first - Then, Burstable pods that exceed their limits - Burstable and Guaranteed pods below their limits are never killed (except if their node fails) - If we only use Guaranteed pods, no pod should ever be killed (as long as they stay within their limits) (Pod QoS is also explained in [this page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/configure-pod-container/quality-service-pod/) of the Kubernetes documentation and in [this blog post](https://medium.com/google-cloud/quality-of-service-class-qos-in-kubernetes-bb76a89eb2c6).) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Where is my swap? - The semantics of memory and swap limits on Linux cgroups are complex - In particular, it's not possible to disable swap for a cgroup (the closest option is to [reduce "swappiness"](https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/77939/turning-off-swapping-for-only-one-process-with-cgroups)) - The architects of Kubernetes wanted to ensure that Guaranteed pods never swap - The only solution was to disable swap entirely .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Alternative point of view - Swap enables paging¹ of anonymous² memory - Even when swap is disabled, Linux will still page memory for: - executables, libraries - mapped files - Disabling swap *will reduce performance and available resources* - For a good time, read [kubernetes/kubernetes#53533](https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/issues/53533) - Also read this [excellent blog post about swap](https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/02/17/mystery-swap/) ¹Paging: reading/writing memory pages from/to disk to reclaim physical memory ²Anonymous memory: memory that is not backed by files or blocks .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Enabling swap anyway - If you don't care that pods are swapping, you can enable swap - You will need to add the flag `--fail-swap-on=false` to kubelet (otherwise, it won't start!) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Specifying resources - Resource requests are expressed at the *container* level - CPU is expressed in "virtual CPUs" (corresponding to the virtual CPUs offered by some cloud providers) - CPU can be expressed with a decimal value, or even a "milli" suffix (so 100m = 0.1) - Memory is expressed in bytes - Memory can be expressed with k, M, G, T, ki, Mi, Gi, Ti suffixes (corresponding to 10^3, 10^6, 10^9, 10^12, 2^10, 2^20, 2^30, 2^40) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Specifying resources in practice This is what the spec of a Pod with resources will look like: ```yaml containers: - name: httpenv image: jpetazzo/httpenv resources: limits: memory: "100Mi" cpu: "100m" requests: memory: "100Mi" cpu: "10m" ``` This set of resources makes sure that this service won't be killed (as long as it stays below 100 MB of RAM), but allows its CPU usage to be throttled if necessary. .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Default values - If we specify a limit without a request: the request is set to the limit - If we specify a request without a limit: there will be no limit (which means that the limit will be the size of the node) - If we don't specify anything: the request is zero and the limit is the size of the node *Unless there are default values defined for our namespace!* .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## We need default resource values - If we do not set resource values at all: - the limit is "the size of the node" - the request is zero - This is generally *not* what we want - a container without a limit can use up all the resources of a node - if the request is zero, the scheduler can't make a smart placement decision - To address this, we can set default values for resources - This is done with a LimitRange object .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources class: title Defining min, max, and default resources .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-resource-limits) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-namespace-quotas) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Defining min, max, and default resources - We can create LimitRange objects to indicate any combination of: - min and/or max resources allowed per pod - default resource *limits* - default resource *requests* - maximal burst ratio (*limit/request*) - LimitRange objects are namespaced - They apply to their namespace only .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## LimitRange example ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: LimitRange metadata: name: my-very-detailed-limitrange spec: limits: - type: Container min: cpu: "100m" max: cpu: "2000m" memory: "1Gi" default: cpu: "500m" memory: "250Mi" defaultRequest: cpu: "500m" ``` .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Example explanation The YAML on the previous slide shows an example LimitRange object specifying very detailed limits on CPU usage, and providing defaults on RAM usage. Note the `type: Container` line: in the future, it might also be possible to specify limits per Pod, but it's not [officially documented yet](https://github.com/kubernetes/website/issues/9585). .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## LimitRange details - LimitRange restrictions are enforced only when a Pod is created (they don't apply retroactively) - They don't prevent creation of e.g. an invalid Deployment or DaemonSet (but the pods will not be created as long as the LimitRange is in effect) - If there are multiple LimitRange restrictions, they all apply together (which means that it's possible to specify conflicting LimitRanges, <br/>preventing any Pod from being created) - If a LimitRange specifies a `max` for a resource but no `default`, <br/>that `max` value becomes the `default` limit too .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-namespace-quotas class: title Namespace quotas .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-defining-min-max-and-default-resources) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Namespace quotas - We can also set quotas per namespace - Quotas apply to the total usage in a namespace (e.g. total CPU limits of all pods in a given namespace) - Quotas can apply to resource limits and/or requests (like the CPU and memory limits that we saw earlier) - Quotas can also apply to other resources: - "extended" resources (like GPUs) - storage size - number of objects (number of pods, services...) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Creating a quota for a namespace - Quotas are enforced by creating a ResourceQuota object - ResourceQuota objects are namespaced, and apply to their namespace only - We can have multiple ResourceQuota objects in the same namespace - The most restrictive values are used .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Limiting total CPU/memory usage - The following YAML specifies an upper bound for *limits* and *requests*: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: ResourceQuota metadata: name: a-little-bit-of-compute spec: hard: requests.cpu: "10" requests.memory: 10Gi limits.cpu: "20" limits.memory: 20Gi ``` These quotas will apply to the namespace where the ResourceQuota is created. .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Limiting number of objects - The following YAML specifies how many objects of specific types can be created: ```yaml apiVersion: v1 kind: ResourceQuota metadata: name: quota-for-objects spec: hard: pods: 100 services: 10 secrets: 10 configmaps: 10 persistentvolumeclaims: 20 services.nodeports: 0 services.loadbalancers: 0 count/roles.rbac.authorization.k8s.io: 10 ``` (The `count/` syntax allows limiting arbitrary objects, including CRDs.) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## YAML vs CLI - Quotas can be created with a YAML definition - ...Or with the `kubectl create quota` command - Example: ```bash kubectl create quota my-resource-quota --hard=pods=300,limits.memory=300Gi ``` - With both YAML and CLI form, the values are always under the `hard` section (there is no `soft` quota) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Viewing current usage When a ResourceQuota is created, we can see how much of it is used: ``` kubectl describe resourcequota my-resource-quota Name: my-resource-quota Namespace: default Resource Used Hard -------- ---- ---- pods 12 100 services 1 5 services.loadbalancers 0 0 services.nodeports 0 0 ``` .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Advanced quotas and PriorityClass - Since Kubernetes 1.12, it is possible to create PriorityClass objects - Pods can be assigned a PriorityClass - Quotas can be linked to a PriorityClass - This allows us to reserve resources for pods within a namespace - For more details, check [this documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/policy/resource-quotas/#resource-quota-per-priorityclass) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-limiting-resources-in-practice class: title Limiting resources in practice .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-namespace-quotas) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-checking-pod-and-node-resource-usage) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Limiting resources in practice - We have at least three mechanisms: - requests and limits per Pod - LimitRange per namespace - ResourceQuota per namespace - Let's see a simple recommendation to get started with resource limits .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Set a LimitRange - In each namespace, create a LimitRange object - Set a small default CPU request and CPU limit (e.g. "100m") - Set a default memory request and limit depending on your most common workload - for Java, Ruby: start with "1G" - for Go, Python, PHP, Node: start with "250M" - Set upper bounds slightly below your expected node size (80-90% of your node size, with at least a 500M memory buffer) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Set a ResourceQuota - In each namespace, create a ResourceQuota object - Set generous CPU and memory limits (e.g. half the cluster size if the cluster hosts multiple apps) - Set generous objects limits - these limits should not be here to constrain your users - they should catch a runaway process creating many resources - example: a custom controller creating many pods .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Observe, refine, iterate - Observe the resource usage of your pods (we will see how in the next chapter) - Adjust individual pod limits - If you see trends: adjust the LimitRange (rather than adjusting every individual set of pod limits) - Observe the resource usage of your namespaces (with `kubectl describe resourcequota ...`) - Rinse and repeat regularly .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- ## Additional resources - [A Practical Guide to Setting Kubernetes Requests and Limits](http://blog.kubecost.com/blog/requests-and-limits/) - explains what requests and limits are - provides guidelines to set requests and limits - gives PromQL expressions to compute good values <br/>(our app needs to be running for a while) - [Kube Resource Report](https://github.com/hjacobs/kube-resource-report/) - generates web reports on resource usage - [static demo](https://hjacobs.github.io/kube-resource-report/sample-report/output/index.html) | [live demo](https://kube-resource-report.demo.j-serv.de/applications.html) .debug[[k8s/resource-limits.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/resource-limits.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-checking-pod-and-node-resource-usage class: title Checking pod and node resource usage .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-limiting-resources-in-practice) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-cluster-sizing) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Checking pod and node resource usage - Since Kubernetes 1.8, metrics are collected by the [resource metrics pipeline](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/debug-application-cluster/resource-metrics-pipeline/) - The resource metrics pipeline is: - optional (Kubernetes can function without it) - necessary for some features (like the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler) - exposed through the Kubernetes API using the [aggregation layer](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/extend-kubernetes/api-extension/apiserver-aggregation/) - usually implemented by the "metrics server" .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## How to know if the metrics server is running? - The easiest way to know is to run `kubectl top` .exercise[ - Check if the core metrics pipeline is available: ```bash kubectl top nodes ``` ] If it shows our nodes and their CPU and memory load, we're good! .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Installing metrics server - The metrics server doesn't have any particular requirements (it doesn't need persistence, as it doesn't *store* metrics) - It has its own repository, [kubernetes-incubator/metrics-server](https://github.com/kubernetes-incubator/metrics-server) - The repository comes with [YAML files for deployment](https://github.com/kubernetes-incubator/metrics-server/tree/master/deploy/1.8%2B) - These files may not work on some clusters (e.g. if your node names are not in DNS) - The container.training repository has a [metrics-server.yaml](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/k8s/metrics-server.yaml#L90) file to help with that (we can `kubectl apply -f` that file if needed) .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- ## Showing container resource usage - Once the metrics server is running, we can check container resource usage .exercise[ - Show resource usage across all containers: ```bash kubectl top pods --containers --all-namespaces ``` ] - We can also use selectors (`-l app=...`) .debug[[k8s/metrics-server.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/metrics-server.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-cluster-sizing class: title Cluster sizing .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-checking-pod-and-node-resource-usage) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-the-horizontal-pod-autoscaler) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Cluster sizing - What happens when the cluster gets full? - How can we scale up the cluster? - Can we do it automatically? - What are other methods to address capacity planning? .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## When are we out of resources? - kubelet monitors node resources: - memory - node disk usage (typically the root filesystem of the node) - image disk usage (where container images and RW layers are stored) - For each resource, we can provide two thresholds: - a hard threshold (if it's met, it provokes immediate action) - a soft threshold (provokes action only after a grace period) - Resource thresholds and grace periods are configurable (by passing kubelet command-line flags) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What happens then? - If disk usage is too high: - kubelet will try to remove terminated pods - then, it will try to *evict* pods - If memory usage is too high: - it will try to evict pods - The node is marked as "under pressure" - This temporarily prevents new pods from being scheduled on the node .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Which pods get evicted? - kubelet looks at the pods' QoS and PriorityClass - First, pods with BestEffort QoS are considered - Then, pods with Burstable QoS exceeding their *requests* (but only if the exceeding resource is the one that is low on the node) - Finally, pods with Guaranteed QoS, and Burstable pods within their requests - Within each group, pods are sorted by PriorityClass - If there are pods with the same PriorityClass, they are sorted by usage excess (i.e. the pods whose usage exceeds their requests the most are evicted first) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Eviction of Guaranteed pods - *Normally*, pods with Guaranteed QoS should not be evicted - A chunk of resources is reserved for node processes (like kubelet) - It is expected that these processes won't use more than this reservation - If they do use more resources anyway, all bets are off! - If this happens, kubelet must evict Guaranteed pods to preserve node stability (or Burstable pods that are still within their requested usage) .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What happens to evicted pods? - The pod is terminated - It is marked as `Failed` at the API level - If the pod was created by a controller, the controller will recreate it - The pod will be recreated on another node, *if there are resources available!* - For more details about the eviction process, see: - [this documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/administer-cluster/out-of-resource/) about resource pressure and pod eviction, - [this other documentation page](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/configuration/pod-priority-preemption/) about pod priority and preemption. .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## What if there are no resources available? - Sometimes, a pod cannot be scheduled anywhere: - all the nodes are under pressure, - or the pod requests more resources than are available - The pod then remains in `Pending` state until the situation improves .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Cluster scaling - One way to improve the situation is to add new nodes - This can be done automatically with the [Cluster Autoscaler](https://github.com/kubernetes/autoscaler/tree/master/cluster-autoscaler) - The autoscaler will automatically scale up: - if there are pods that failed to be scheduled - The autoscaler will automatically scale down: - if nodes have a low utilization for an extended period of time .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Restrictions, gotchas ... - The Cluster Autoscaler only supports a few cloud infrastructures (see [here](https://github.com/kubernetes/autoscaler/tree/master/cluster-autoscaler/cloudprovider) for a list) - The Cluster Autoscaler cannot scale down nodes that have pods using: - local storage - affinity/anti-affinity rules preventing them from being rescheduled - a restrictive PodDisruptionBudget .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- ## Other way to do capacity planning - "Running Kubernetes without nodes" - Systems like [Virtual Kubelet](https://virtual-kubelet.io/) or [Kiyot](https://static.elotl.co/docs/latest/kiyot/kiyot.html) can run pods using on-demand resources - Virtual Kubelet can leverage e.g. ACI or Fargate to run pods - Kiyot runs pods in ad-hoc EC2 instances (1 instance per pod) - Economic advantage (no wasted capacity) - Security advantage (stronger isolation between pods) Check [this blog post](http://jpetazzo.github.io/2019/02/13/running-kubernetes-without-nodes-with-kiyot/) for more details. .debug[[k8s/cluster-sizing.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/cluster-sizing.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-the-horizontal-pod-autoscaler class: title The Horizontal Pod Autoscaler .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-cluster-sizing) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-3) | [Next section](#toc-collecting-metrics-with-prometheus) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # The Horizontal Pod Autoscaler - What is the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler, or HPA? - It is a controller that can perform *horizontal* scaling automatically - Horizontal scaling = changing the number of replicas (adding/removing pods) - Vertical scaling = changing the size of individual replicas (increasing/reducing CPU and RAM per pod) - Cluster scaling = changing the size of the cluster (adding/removing nodes) .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Principle of operation - Each HPA resource (or "policy") specifies: - which object to monitor and scale (e.g. a Deployment, ReplicaSet...) - min/max scaling ranges (the max is a safety limit!) - a target resource usage (e.g. the default is CPU=80%) - The HPA continuously monitors the CPU usage for the related object - It computes how many pods should be running: `TargetNumOfPods = ceil(sum(CurrentPodsCPUUtilization) / Target)` - It scales the related object up/down to this target number of pods .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Pre-requirements - The metrics server needs to be running (i.e. we need to be able to see pod metrics with `kubectl top pods`) - The pods that we want to autoscale need to have resource requests (because the target CPU% is not absolute, but relative to the request) - The latter actually makes a lot of sense: - if a Pod doesn't have a CPU request, it might be using 10% of CPU... - ...but only because there is no CPU time available! - this makes sure that we won't add pods to nodes that are already resource-starved .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Testing the HPA - We will start a CPU-intensive web service - We will send some traffic to that service - We will create an HPA policy - The HPA will automatically scale up the service for us .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## A CPU-intensive web service - Let's use `jpetazzo/busyhttp` (it is a web server that will use 1s of CPU for each HTTP request) .exercise[ - Deploy the web server: ```bash kubectl create deployment busyhttp --image=jpetazzo/busyhttp ``` - Expose it with a ClusterIP service: ```bash kubectl expose deployment busyhttp --port=80 ``` - Get the ClusterIP allocated to the service: ```bash kubectl get svc busyhttp ``` ] .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Monitor what's going on - Let's start a bunch of commands to watch what is happening .exercise[ - Monitor pod CPU usage: ```bash watch kubectl top pods -l app=busyhttp ``` <!-- ```wait NAME``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` ```bash CLUSTERIP=$(kubectl get svc busyhttp -o jsonpath={.spec.clusterIP})``` --> - Monitor service latency: ```bash httping http://`$CLUSTERIP`/ ``` <!-- ```wait connected to``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` --> - Monitor cluster events: ```bash kubectl get events -w ``` <!-- ```wait Normal``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` ```bash CLUSTERIP=$(kubectl get svc busyhttp -o jsonpath={.spec.clusterIP})``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Send traffic to the service - We will use `ab` (Apache Bench) to send traffic .exercise[ - Send a lot of requests to the service, with a concurrency level of 3: ```bash ab -c 3 -n 100000 http://`$CLUSTERIP`/ ``` <!-- ```wait be patient``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` ```tmux selectl even-vertical``` --> ] The latency (reported by `httping`) should increase above 3s. The CPU utilization should increase to 100%. (The server is single-threaded and won't go above 100%.) .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Create an HPA policy - There is a helper command to do that for us: `kubectl autoscale` .exercise[ - Create the HPA policy for the `busyhttp` deployment: ```bash kubectl autoscale deployment busyhttp --max=10 ``` ] By default, it will assume a target of 80% CPU usage. This can also be set with `--cpu-percent=`. -- *The autoscaler doesn't seem to work. Why?* .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## What did we miss? - The events stream gives us a hint, but to be honest, it's not very clear: `missing request for cpu` - We forgot to specify a resource request for our Deployment! - The HPA target is not an absolute CPU% - It is relative to the CPU requested by the pod .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Adding a CPU request - Let's edit the deployment and add a CPU request - Since our server can use up to 1 core, let's request 1 core .exercise[ - Edit the Deployment definition: ```bash kubectl edit deployment busyhttp ``` <!-- ```wait Please edit``` ```keys /resources``` ```key ^J``` ```keys $xxxo requests:``` ```key ^J``` ```key Space``` ```key Space``` ```keys cpu: "1"``` ```key Escape``` ```keys :wq``` ```key ^J``` --> - In the `containers` list, add the following block: ```yaml resources: requests: cpu: "1" ``` ] .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Results - After saving and quitting, a rolling update happens (if `ab` or `httping` exits, make sure to restart it) - It will take a minute or two for the HPA to kick in: - the HPA runs every 30 seconds by default - it needs to gather metrics from the metrics server first - If we scale further up (or down), the HPA will react after a few minutes: - it won't scale up if it already scaled in the last 3 minutes - it won't scale down if it already scaled in the last 5 minutes .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## What about other metrics? - The HPA in API group `autoscaling/v1` only supports CPU scaling - The HPA in API group `autoscaling/v2beta2` supports metrics from various API groups: - metrics.k8s.io, aka metrics server (per-Pod CPU and RAM) - custom.metrics.k8s.io, custom metrics per Pod - external.metrics.k8s.io, external metrics (not associated to Pods) - Kubernetes doesn't implement any of these API groups - Using these metrics requires [registering additional APIs](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/run-application/horizontal-pod-autoscale/#support-for-metrics-apis) - The metrics provided by metrics server are standard; everything else is custom - For more details, see [this great blog post](https://medium.com/uptime-99/kubernetes-hpa-autoscaling-with-custom-and-external-metrics-da7f41ff7846) or [this talk](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gSiGFH4ZnS8) .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- ## Cleanup - Since `busyhttp` uses CPU cycles, let's stop it before moving on .exercise[ - Delete the `busyhttp` Deployment: ```bash kubectl delete deployment busyhttp ``` <!-- ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/horizontal-pod-autoscaler.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-collecting-metrics-with-prometheus class: title Collecting metrics with Prometheus .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-the-horizontal-pod-autoscaler) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-4) | [Next section](#toc-centralized-logging) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Collecting metrics with Prometheus - Prometheus is an open-source monitoring system including: - multiple *service discovery* backends to figure out which metrics to collect - a *scraper* to collect these metrics - an efficient *time series database* to store these metrics - a specific query language (PromQL) to query these time series - an *alert manager* to notify us according to metrics values or trends - We are going to use it to collect and query some metrics on our Kubernetes cluster .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Why Prometheus? - We don't endorse Prometheus more or less than any other system - It's relatively well integrated within the cloud-native ecosystem - It can be self-hosted (this is useful for tutorials like this) - It can be used for deployments of varying complexity: - one binary and 10 lines of configuration to get started - all the way to thousands of nodes and millions of metrics .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Exposing metrics to Prometheus - Prometheus obtains metrics and their values by querying *exporters* - An exporter serves metrics over HTTP, in plain text - This is what the *node exporter* looks like: http://demo.robustperception.io:9100/metrics - Prometheus itself exposes its own internal metrics, too: http://demo.robustperception.io:9090/metrics - If you want to expose custom metrics to Prometheus: - serve a text page like these, and you're good to go - libraries are available in various languages to help with quantiles etc. .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## How Prometheus gets these metrics - The *Prometheus server* will *scrape* URLs like these at regular intervals (by default: every minute; can be more/less frequent) - The list of URLs to scrape (the *scrape targets*) is defined in configuration .footnote[Worried about the overhead of parsing a text format? <br/> Check this [comparison](https://github.com/RichiH/OpenMetrics/blob/master/markdown/protobuf_vs_text.md) of the text format with the (now deprecated) protobuf format!] .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Defining scrape targets This is maybe the simplest configuration file for Prometheus: ```yaml scrape_configs: - job_name: 'prometheus' static_configs: - targets: ['localhost:9090'] ``` - In this configuration, Prometheus collects its own internal metrics - A typical configuration file will have multiple `scrape_configs` - In this configuration, the list of targets is fixed - A typical configuration file will use dynamic service discovery .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Service discovery This configuration file will leverage existing DNS `A` records: ```yaml scrape_configs: - ... - job_name: 'node' dns_sd_configs: - names: ['api-backends.dc-paris-2.enix.io'] type: 'A' port: 9100 ``` - In this configuration, Prometheus resolves the provided name(s) (here, `api-backends.dc-paris-2.enix.io`) - Each resulting IP address is added as a target on port 9100 .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Dynamic service discovery - In the DNS example, the names are re-resolved at regular intervals - As DNS records are created/updated/removed, scrape targets change as well - Existing data (previously collected metrics) is not deleted - Other service discovery backends work in a similar fashion .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Other service discovery mechanisms - Prometheus can connect to e.g. a cloud API to list instances - Or to the Kubernetes API to list nodes, pods, services ... - Or a service like Consul, Zookeeper, etcd, to list applications - The resulting configurations files are *way more complex* (but don't worry, we won't need to write them ourselves) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Time series database - We could wonder, "why do we need a specialized database?" - One metrics data point = metrics ID + timestamp + value - With a classic SQL or noSQL data store, that's at least 160 bits of data + indexes - Prometheus is way more efficient, without sacrificing performance (it will even be gentler on the I/O subsystem since it needs to write less) - Would you like to know more? Check this video: [Storage in Prometheus 2.0](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C4YV-9CrawA) by [Goutham V](https://twitter.com/putadent) at DC17EU .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Checking if Prometheus is installed - Before trying to install Prometheus, let's check if it's already there .exercise[ - Look for services with a label `app=prometheus` across all namespaces: ```bash kubectl get services --selector=app=prometheus --all-namespaces ``` ] If we see a `NodePort` service called `prometheus-server`, we're good! (We can then skip to "Connecting to the Prometheus web UI".) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Running Prometheus on our cluster We need to: - Run the Prometheus server in a pod (using e.g. a Deployment to ensure that it keeps running) - Expose the Prometheus server web UI (e.g. with a NodePort) - Run the *node exporter* on each node (with a Daemon Set) - Set up a Service Account so that Prometheus can query the Kubernetes API - Configure the Prometheus server (storing the configuration in a Config Map for easy updates) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Helm charts to the rescue - To make our lives easier, we are going to use a Helm chart - The Helm chart will take care of all the steps explained above (including some extra features that we don't need, but won't hurt) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Step 1: install Helm - If we already installed Helm earlier, this command won't break anything .exercise[ - Install the Helm CLI: ```bash curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/kubernetes/helm/master/scripts/get-helm-3 \ | bash ``` ] .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Step 2: add the `stable` repo - This will add the repository containing the chart for Prometheus - This command is idempotent (it won't break anything if the repository was already added) .exercise[ - Add the repository: ```bash helm repo add stable https://kubernetes-charts.storage.googleapis.com/ ``` ] .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Step 3: install Prometheus - The following command, just like the previous ones, is idempotent (it won't error out if Prometheus is already installed) .exercise[ - Install Prometheus on our cluster: ```bash helm upgrade prometheus stable/prometheus \ --install \ --namespace kube-system \ --set server.service.type=NodePort \ --set server.service.nodePort=30090 \ --set server.persistentVolume.enabled=false \ --set alertmanager.enabled=false ``` ] Curious about all these flags? They're explained in the next slide. .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Explaining all the Helm flags - `helm upgrade prometheus` → upgrade release "prometheus" to the latest version... (a "release" is a unique name given to an app deployed with Helm) - `stable/prometheus` → ... of the chart `prometheus` in repo `stable` - `--install` → if the app doesn't exist, create it - `--namespace kube-system` → put it in that specific namespace - And set the following *values* when rendering the chart's templates: - `server.service.type=NodePort` → expose the Prometheus server with a NodePort - `server.service.nodePort=30090` → set the specific NodePort number to use - `server.persistentVolume.enabled=false` → do not use a PersistentVolumeClaim - `alertmanager.enabled=false` → disable the alert manager entirely .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Connecting to the Prometheus web UI - Let's connect to the web UI and see what we can do .exercise[ - Figure out the NodePort that was allocated to the Prometheus server: ```bash kubectl get svc --all-namespaces | grep prometheus-server ``` - With your browser, connect to that port ] .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Querying some metrics - This is easy... if you are familiar with PromQL .exercise[ - Click on "Graph", and in "expression", paste the following: ``` sum by (instance) ( irate( container_cpu_usage_seconds_total{ pod_name=~"worker.*" }[5m] ) ) ``` ] - Click on the blue "Execute" button and on the "Graph" tab just below - We see the cumulated CPU usage of worker pods for each node <br/> (if we just deployed Prometheus, there won't be much data to see, though) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Getting started with PromQL - We can't learn PromQL in just 5 minutes - But we can cover the basics to get an idea of what is possible (and have some keywords and pointers) - We are going to break down the query above (building it one step at a time) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Graphing one metric across all tags This query will show us CPU usage across all containers: ``` container_cpu_usage_seconds_total ``` - The suffix of the metrics name tells us: - the unit (seconds of CPU) - that it's the total used since the container creation - Since it's a "total," it is an increasing quantity (we need to compute the derivative if we want e.g. CPU % over time) - We see that the metrics retrieved have *tags* attached to them .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Selecting metrics with tags This query will show us only metrics for worker containers: ``` container_cpu_usage_seconds_total{pod_name=~"worker.*"} ``` - The `=~` operator allows regex matching - We select all the pods with a name starting with `worker` (it would be better to use labels to select pods; more on that later) - The result is a smaller set of containers .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Transforming counters in rates This query will show us CPU usage % instead of total seconds used: ``` 100*irate(container_cpu_usage_seconds_total{pod_name=~"worker.*"}[5m]) ``` - The [`irate`](https://prometheus.io/docs/prometheus/latest/querying/functions/#irate) operator computes the "per-second instant rate of increase" - `rate` is similar but allows decreasing counters and negative values - with `irate`, if a counter goes back to zero, we don't get a negative spike - The `[5m]` tells how far to look back if there is a gap in the data - And we multiply with `100*` to get CPU % usage .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Aggregation operators This query sums the CPU usage per node: ``` sum by (instance) ( irate(container_cpu_usage_seconds_total{pod_name=~"worker.*"}[5m]) ) ``` - `instance` corresponds to the node on which the container is running - `sum by (instance) (...)` computes the sum for each instance - Note: all the other tags are collapsed (in other words, the resulting graph only shows the `instance` tag) - PromQL supports many more [aggregation operators](https://prometheus.io/docs/prometheus/latest/querying/operators/#aggregation-operators) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## What kind of metrics can we collect? - Node metrics (related to physical or virtual machines) - Container metrics (resource usage per container) - Databases, message queues, load balancers, ... (check out this [list of exporters](https://prometheus.io/docs/instrumenting/exporters/)!) - Instrumentation (=deluxe `printf` for our code) - Business metrics (customers served, revenue, ...) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Node metrics - CPU, RAM, disk usage on the whole node - Total number of processes running, and their states - Number of open files, sockets, and their states - I/O activity (disk, network), per operation or volume - Physical/hardware (when applicable): temperature, fan speed... - ...and much more! .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Container metrics - Similar to node metrics, but not totally identical - RAM breakdown will be different - active vs inactive memory - some memory is *shared* between containers, and specially accounted for - I/O activity is also harder to track - async writes can cause deferred "charges" - some page-ins are also shared between containers For details about container metrics, see: <br/> http://jpetazzo.github.io/2013/10/08/docker-containers-metrics/ .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Application metrics - Arbitrary metrics related to your application and business - System performance: request latency, error rate... - Volume information: number of rows in database, message queue size... - Business data: inventory, items sold, revenue... .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Detecting scrape targets - Prometheus can leverage Kubernetes service discovery (with proper configuration) - Services or pods can be annotated with: - `prometheus.io/scrape: true` to enable scraping - `prometheus.io/port: 9090` to indicate the port number - `prometheus.io/path: /metrics` to indicate the URI (`/metrics` by default) - Prometheus will detect and scrape these (without needing a restart or reload) .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Querying labels - What if we want to get metrics for containers belonging to a pod tagged `worker`? - The cAdvisor exporter does not give us Kubernetes labels - Kubernetes labels are exposed through another exporter - We can see Kubernetes labels through metrics `kube_pod_labels` (each container appears as a time series with constant value of `1`) - Prometheus *kind of* supports "joins" between time series - But only if the names of the tags match exactly .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## Unfortunately ... - The cAdvisor exporter uses tag `pod_name` for the name of a pod - The Kubernetes service endpoints exporter uses tag `pod` instead - See [this blog post](https://www.robustperception.io/exposing-the-software-version-to-prometheus) or [this other one](https://www.weave.works/blog/aggregating-pod-resource-cpu-memory-usage-arbitrary-labels-prometheus/) to see how to perform "joins" - Alas, Prometheus cannot "join" time series with different labels (see [Prometheus issue #2204](https://github.com/prometheus/prometheus/issues/2204) for the rationale) - There is a workaround involving relabeling, but it's "not cheap" - see [this comment](https://github.com/prometheus/prometheus/issues/2204#issuecomment-261515520) for an overview - or [this blog post](https://5pi.de/2017/11/09/use-prometheus-vector-matching-to-get-kubernetes-utilization-across-any-pod-label/) for a complete description of the process .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- ## In practice - Grafana is a beautiful (and useful) frontend to display all kinds of graphs - Not everyone needs to know Prometheus, PromQL, Grafana, etc. - But in a team, it is valuable to have at least one person who know them - That person can set up queries and dashboards for the rest of the team - It's a little bit like knowing how to optimize SQL queries, Dockerfiles... Don't panic if you don't know these tools! ...But make sure at least one person in your team is on it 💯 .debug[[k8s/prometheus.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/prometheus.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-centralized-logging class: title Centralized logging .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-collecting-metrics-with-prometheus) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-4) | [Next section](#toc-extending-the-kubernetes-api) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Centralized logging - Using `kubectl` or `stern` is simple; but it has drawbacks: - when a node goes down, its logs are not available anymore - we can only dump or stream logs; we want to search/index/count... - We want to send all our logs to a single place - We want to parse them (e.g. for HTTP logs) and index them - We want a nice web dashboard -- - We are going to deploy an EFK stack .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## What is EFK? - EFK is three components: - ElasticSearch (to store and index log entries) - Fluentd (to get container logs, process them, and put them in ElasticSearch) - Kibana (to view/search log entries with a nice UI) - The only component that we need to access from outside the cluster will be Kibana .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## Deploying EFK on our cluster - We are going to use a YAML file describing all the required resources .exercise[ - Load the YAML file into our cluster: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/efk.yaml ``` ] If we [look at the YAML file](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/blob/master/k8s/efk.yaml), we see that it creates a daemon set, two deployments, two services, and a few roles and role bindings (to give fluentd the required permissions). .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## The itinerary of a log line (before Fluentd) - A container writes a line on stdout or stderr - Both are typically piped to the container engine (Docker or otherwise) - The container engine reads the line, and sends it to a logging driver - The timestamp and stream (stdout or stderr) is added to the log line - With the default configuration for Kubernetes, the line is written to a JSON file (`/var/log/containers/pod-name_namespace_container-id.log`) - That file is read when we invoke `kubectl logs`; we can access it directly too .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## The itinerary of a log line (with Fluentd) - Fluentd runs on each node (thanks to a daemon set) - It bind-mounts `/var/log/containers` from the host (to access these files) - It continuously scans this directory for new files; reads them; parses them - Each log line becomes a JSON object, fully annotated with extra information: <br/>container id, pod name, Kubernetes labels... - These JSON objects are stored in ElasticSearch - ElasticSearch indexes the JSON objects - We can access the logs through Kibana (and perform searches, counts, etc.) .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## Accessing Kibana - Kibana offers a web interface that is relatively straightforward - Let's check it out! .exercise[ - Check which `NodePort` was allocated to Kibana: ```bash kubectl get svc kibana ``` - With our web browser, connect to Kibana ] .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## Using Kibana *Note: this is not a Kibana workshop! So this section is deliberately very terse.* - The first time you connect to Kibana, you must "configure an index pattern" - Just use the one that is suggested, `@timestamp`.red[*] - Then click "Discover" (in the top-left corner) - You should see container logs - Advice: in the left column, select a few fields to display, e.g.: `kubernetes.host`, `kubernetes.pod_name`, `stream`, `log` .red[*]If you don't see `@timestamp`, it's probably because no logs exist yet. <br/>Wait a bit, and double-check the logging pipeline! .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- ## Caveat emptor We are using EFK because it is relatively straightforward to deploy on Kubernetes, without having to redeploy or reconfigure our cluster. But it doesn't mean that it will always be the best option for your use-case. If you are running Kubernetes in the cloud, you might consider using the cloud provider's logging infrastructure (if it can be integrated with Kubernetes). The deployment method that we will use here has been simplified: there is only one ElasticSearch node. In a real deployment, you might use a cluster, both for performance and reliability reasons. But this is outside of the scope of this chapter. The YAML file that we used creates all the resources in the `default` namespace, for simplicity. In a real scenario, you will create the resources in the `kube-system` namespace or in a dedicated namespace. .debug[[k8s/logs-centralized.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/logs-centralized.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-extending-the-kubernetes-api class: title Extending the Kubernetes API .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-centralized-logging) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-4) | [Next section](#toc-operators) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Extending the Kubernetes API There are multiple ways to extend the Kubernetes API. We are going to cover: - Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) - Admission Webhooks - The Aggregation Layer .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Revisiting the API server - The Kubernetes API server is a central point of the control plane (everything connects to it: controller manager, scheduler, kubelets) - Almost everything in Kubernetes is materialized by a resource - Resources have a type (or "kind") (similar to strongly typed languages) - We can see existing types with `kubectl api-resources` - We can list resources of a given type with `kubectl get <type>` .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Creating new types - We can create new types with Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) - CRDs are created dynamically (without recompiling or restarting the API server) - CRDs themselves are resources: - we can create a new type with `kubectl create` and some YAML - we can see all our custom types with `kubectl get crds` - After we create a CRD, the new type works just like built-in types .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## A very simple CRD The YAML below describes a very simple CRD representing different kinds of coffee: ```yaml apiVersion: apiextensions.k8s.io/v1alpha1 kind: CustomResourceDefinition metadata: name: coffees.container.training spec: group: container.training version: v1alpha1 scope: Namespaced names: plural: coffees singular: coffee kind: Coffee shortNames: - cof ``` .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Creating a CRD - Let's create the Custom Resource Definition for our Coffee resource .exercise[ - Load the CRD: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/coffee-1.yaml ``` - Confirm that it shows up: ```bash kubectl get crds ``` ] .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Creating custom resources The YAML below defines a resource using the CRD that we just created: ```yaml kind: Coffee apiVersion: container.training/v1alpha1 metadata: name: arabica spec: taste: strong ``` .exercise[ - Create a few types of coffee beans: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/coffees.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Viewing custom resources - By default, `kubectl get` only shows name and age of custom resources .exercise[ - View the coffee beans that we just created: ```bash kubectl get coffees ``` ] - We can improve that, but it's outside the scope of this section! .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## What can we do with CRDs? There are many possibilities! - *Operators* encapsulate complex sets of resources (e.g.: a PostgreSQL replicated cluster; an etcd cluster... <br/> see [awesome operators](https://github.com/operator-framework/awesome-operators) and [OperatorHub](https://operatorhub.io/) to find more) - Custom use-cases like [gitkube](https://gitkube.sh/) - creates a new custom type, `Remote`, exposing a git+ssh server - deploy by pushing YAML or Helm charts to that remote - Replacing built-in types with CRDs (see [this lightning talk by Tim Hockin](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ji0FWzFwNhA)) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Little details - By default, CRDs are not *validated* (we can put anything we want in the `spec`) - When creating a CRD, we can pass an OpenAPI v3 schema (BETA!) (which will then be used to validate resources) - Generally, when creating a CRD, we also want to run a *controller* (otherwise nothing will happen when we create resources of that type) - The controller will typically *watch* our custom resources (and take action when they are created/updated) * Examples: [YAML to install the gitkube CRD](https://storage.googleapis.com/gitkube/gitkube-setup-stable.yaml), [YAML to install a redis operator CRD](https://github.com/amaizfinance/redis-operator/blob/master/deploy/crds/k8s_v1alpha1_redis_crd.yaml) * .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## (Ab)using the API server - If we need to store something "safely" (as in: in etcd), we can use CRDs - This gives us primitives to read/write/list objects (and optionally validate them) - The Kubernetes API server can run on its own (without the scheduler, controller manager, and kubelets) - By loading CRDs, we can have it manage totally different objects (unrelated to containers, clusters, etc.) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Service catalog - *Service catalog* is another extension mechanism - It's not extending the Kubernetes API strictly speaking (but it still provides new features!) - It doesn't create new types; it uses: - ClusterServiceBroker - ClusterServiceClass - ClusterServicePlan - ServiceInstance - ServiceBinding - It uses the Open service broker API .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Admission controllers - Admission controllers are another way to extend the Kubernetes API - Instead of creating new types, admission controllers can transform or vet API requests - The diagram on the next slide shows the path of an API request (courtesy of Banzai Cloud) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- class: pic  .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Types of admission controllers - *Validating* admission controllers can accept/reject the API call - *Mutating* admission controllers can modify the API request payload - Both types can also trigger additional actions (e.g. automatically create a Namespace if it doesn't exist) - There are a number of built-in admission controllers (see [documentation](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/admission-controllers/#what-does-each-admission-controller-do) for a list) - We can also dynamically define and register our own .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Some built-in admission controllers - ServiceAccount: automatically adds a ServiceAccount to Pods that don't explicitly specify one - LimitRanger: applies resource constraints specified by LimitRange objects when Pods are created - NamespaceAutoProvision: automatically creates namespaces when an object is created in a non-existent namespace *Note: #1 and #2 are enabled by default; #3 is not.* .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Admission Webhooks - We can setup *admission webhooks* to extend the behavior of the API server - The API server will submit incoming API requests to these webhooks - These webhooks can be *validating* or *mutating* - Webhooks can be set up dynamically (without restarting the API server) - To setup a dynamic admission webhook, we create a special resource: a `ValidatingWebhookConfiguration` or a `MutatingWebhookConfiguration` - These resources are created and managed like other resources (i.e. `kubectl create`, `kubectl get`...) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Webhook Configuration - A ValidatingWebhookConfiguration or MutatingWebhookConfiguration contains: - the address of the webhook - the authentication information to use with the webhook - a list of rules - The rules indicate for which objects and actions the webhook is triggered (to avoid e.g. triggering webhooks when setting up webhooks) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## The aggregation layer - We can delegate entire parts of the Kubernetes API to external servers - This is done by creating APIService resources (check them with `kubectl get apiservices`!) - The APIService resource maps a type (kind) and version to an external service - All requests concerning that type are sent (proxied) to the external service - This allows to have resources like CRDs, but that aren't stored in etcd - Example: `metrics-server` (storing live metrics in etcd would be extremely inefficient) - Requires significantly more work than CRDs! .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- ## Documentation - [Custom Resource Definitions: when to use them](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/extend-kubernetes/api-extension/custom-resources/) - [Custom Resources Definitions: how to use them](https://kubernetes.io/docs/tasks/access-kubernetes-api/custom-resources/custom-resource-definitions/) - [Service Catalog](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/extend-kubernetes/service-catalog/) - [Built-in Admission Controllers](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/admission-controllers/) - [Dynamic Admission Controllers](https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/extensible-admission-controllers/) - [Aggregation Layer](https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/extend-kubernetes/api-extension/apiserver-aggregation/) .debug[[k8s/extending-api.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/extending-api.md)] --- class: pic .interstitial[] --- name: toc-operators class: title Operators .nav[ [Previous section](#toc-extending-the-kubernetes-api) | [Back to table of contents](#toc-chapter-4) | [Next section](#toc-) ] .debug[(automatically generated title slide)] --- # Operators - Operators are one of the many ways to extend Kubernetes - We will define operators - We will see how they work - We will install a specific operator (for ElasticSearch) - We will use it to provision an ElasticSearch cluster .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## What are operators? *An operator represents **human operational knowledge in software,** <br/> to reliably manage an application. — [CoreOS](https://coreos.com/blog/introducing-operators.html)* Examples: - Deploying and configuring replication with MySQL, PostgreSQL ... - Setting up Elasticsearch, Kafka, RabbitMQ, Zookeeper ... - Reacting to failures when intervention is needed - Scaling up and down these systems .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## What are they made from? - Operators combine two things: - Custom Resource Definitions - controller code watching the corresponding resources and acting upon them - A given operator can define one or multiple CRDs - The controller code (control loop) typically runs within the cluster (running as a Deployment with 1 replica is a common scenario) - But it could also run elsewhere (nothing mandates that the code run on the cluster, as long as it has API access) .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Why use operators? - Kubernetes gives us Deployments, StatefulSets, Services ... - These mechanisms give us building blocks to deploy applications - They work great for services that are made of *N* identical containers (like stateless ones) - They also work great for some stateful applications like Consul, etcd ... (with the help of highly persistent volumes) - They're not enough for complex services: - where different containers have different roles - where extra steps have to be taken when scaling or replacing containers .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Use-cases for operators - Systems with primary/secondary replication Examples: MariaDB, MySQL, PostgreSQL, Redis ... - Systems where different groups of nodes have different roles Examples: ElasticSearch, MongoDB ... - Systems with complex dependencies (that are themselves managed with operators) Examples: Flink or Kafka, which both depend on Zookeeper .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## More use-cases - Representing and managing external resources (Example: [AWS Service Operator](https://operatorhub.io/operator/alpha/aws-service-operator.v0.0.1)) - Managing complex cluster add-ons (Example: [Istio operator](https://operatorhub.io/operator/beta/istio-operator.0.1.6)) - Deploying and managing our applications' lifecycles (more on that later) .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## How operators work - An operator creates one or more CRDs (i.e., it creates new "Kinds" of resources on our cluster) - The operator also runs a *controller* that will watch its resources - Each time we create/update/delete a resource, the controller is notified (we could write our own cheap controller with `kubectl get --watch`) .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## One operator in action - We will install [Elastic Cloud on Kubernetes](https://www.elastic.co/guide/en/cloud-on-k8s/current/k8s-quickstart.html), an ElasticSearch operator - This operator requires PersistentVolumes - We will install Rancher's [local path storage provisioner](https://github.com/rancher/local-path-provisioner) to automatically create these - Then, we will create an ElasticSearch resource - The operator will detect that resource and provision the cluster .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Installing a Persistent Volume provisioner (This step can be skipped if you already have a dynamic volume provisioner.) - This provisioner creates Persistent Volumes backed by `hostPath` (local directories on our nodes) - It doesn't require anything special ... - ... But losing a node = losing the volumes on that node! .exercise[ - Install the local path storage provisioner: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/local-path-storage.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Making sure we have a default StorageClass - The ElasticSearch operator will create StatefulSets - These StatefulSets will instantiate PersistentVolumeClaims - These PVCs need to be explicitly associated with a StorageClass - Or we need to tag a StorageClass to be used as the default one .exercise[ - List StorageClasses: ```bash kubectl get storageclasses ``` ] We should see the `local-path` StorageClass. .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Setting a default StorageClass - This is done by adding an annotation to the StorageClass: `storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class: true` .exercise[ - Tag the StorageClass so that it's the default one: ```bash kubectl annotate storageclass local-path \ storageclass.kubernetes.io/is-default-class=true ``` - Check the result: ```bash kubectl get storageclasses ``` ] Now, the StorageClass should have `(default)` next to its name. .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Install the ElasticSearch operator - The operator provides: - a few CustomResourceDefinitions - a Namespace for its other resources - a ValidatingWebhookConfiguration for type checking - a StatefulSet for its controller and webhook code - a ServiceAccount, ClusterRole, ClusterRoleBinding for permissions - All these resources are grouped in a convenient YAML file .exercise[ - Install the operator: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/eck-operator.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Check our new custom resources - Let's see which CRDs were created .exercise[ - List all CRDs: ```bash kubectl get crds ``` ] This operator supports ElasticSearch, but also Kibana and APM. Cool! .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Create the `eck-demo` namespace - For clarity, we will create everything in a new namespace, `eck-demo` - This namespace is hard-coded in the YAML files that we are going to use - We need to create that namespace .exercise[ - Create the `eck-demo` namespace: ```bash kubectl create namespace eck-demo ``` - Switch to that namespace: ```bash kns eck-demo ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- class: extra-details ## Can we use a different namespace? Yes, but then we need to update all the YAML manifests that we are going to apply in the next slides. The `eck-demo` namespace is hard-coded in these YAML manifests. Why? Because when defining a ClusterRoleBinding that references a ServiceAccount, we have to indicate in which namespace the ServiceAccount is located. .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Create an ElasticSearch resource - We can now create a resource with `kind: ElasticSearch` - The YAML for that resource will specify all the desired parameters: - how many nodes we want - image to use - add-ons (kibana, cerebro, ...) - whether to use TLS or not - etc. .exercise[ - Create our ElasticSearch cluster: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/eck-elasticsearch.yaml ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Operator in action - Over the next minutes, the operator will create our ES cluster - It will report our cluster status through the CRD .exercise[ - Check the logs of the operator: ```bash stern --namespace=elastic-system operator ``` <!-- ```wait elastic-operator-0``` ```tmux split-pane -v``` ---> - Watch the status of the cluster through the CRD: ```bash kubectl get es -w ``` <!-- ```longwait green``` ```key ^C``` ```key ^D``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Connecting to our cluster - It's not easy to use the ElasticSearch API from the shell - But let's check at least if ElasticSearch is up! .exercise[ - Get the ClusterIP of our ES instance: ```bash kubectl get services ``` - Issue a request with `curl`: ```bash curl http://`CLUSTERIP`:9200 ``` ] We get an authentication error. Our cluster is protected! .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Obtaining the credentials - The operator creates a user named `elastic` - It generates a random password and stores it in a Secret .exercise[ - Extract the password: ```bash kubectl get secret demo-es-elastic-user \ -o go-template="{{ .data.elastic | base64decode }} " ``` - Use it to connect to the API: ```bash curl -u elastic:`PASSWORD` http://`CLUSTERIP`:9200 ``` ] We should see a JSON payload with the `"You Know, for Search"` tagline. .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Sending data to the cluster - Let's send some data to our brand new ElasticSearch cluster! - We'll deploy a filebeat DaemonSet to collect node logs .exercise[ - Deploy filebeat: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/eck-filebeat.yaml ``` - Wait until some pods are up: ```bash watch kubectl get pods -l k8s-app=filebeat ``` <!-- ```wait Running``` ```key ^C``` --> - Check that a filebeat index was created: ```bash curl -u elastic:`PASSWORD` http://`CLUSTERIP`:9200/_cat/indices ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Deploying an instance of Kibana - Kibana can visualize the logs injected by filebeat - The ECK operator can also manage Kibana - Let's give it a try! .exercise[ - Deploy a Kibana instance: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/eck-kibana.yaml ``` - Wait for it to be ready: ```bash kubectl get kibana -w ``` <!-- ```longwait green``` ```key ^C``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Connecting to Kibana - Kibana is automatically set up to conect to ElasticSearch (this is arranged by the YAML that we're using) - However, it will ask for authentication - It's using the same user/password as ElasticSearch .exercise[ - Get the NodePort allocated to Kibana: ```bash kubectl get services ``` - Connect to it with a web browser - Use the same user/password as before ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Setting up Kibana After the Kibana UI loads, we need to click around a bit .exercise[ - Pick "explore on my own" - Click on Use Elasticsearch data / Connect to your Elasticsearch index" - Enter `filebeat-*` for the index pattern and click "Next step" - Select `@timestamp` as time filter field name - Click on "discover" (the small icon looking like a compass on the left bar) - Play around! ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Scaling up the cluster - At this point, we have only one node - We are going to scale up - But first, we'll deploy Cerebro, an UI for ElasticSearch - This will let us see the state of the cluster, how indexes are sharded, etc. .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Deploying Cerebro - Cerebro is stateless, so it's fairly easy to deploy (one Deployment + one Service) - However, it needs the address and credentials for ElasticSearch - We prepared yet another manifest for that! .exercise[ - Deploy Cerebro: ```bash kubectl apply -f ~/container.training/k8s/eck-cerebro.yaml ``` - Lookup the NodePort number and connect to it: ```bash kubectl get services ``` ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Scaling up the cluster - We can see on Cerebro that the cluster is "yellow" (because our index is not replicated) - Let's change that! .exercise[ - Edit the ElasticSearch cluster manifest: ```bash kubectl edit es demo ``` - Find the field `count: 1` and change it to 3 - Save and quit <!-- ```wait Please edit``` ```keys /count:``` ```key ^J``` ```keys $r3:x``` ```key ^J``` --> ] .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Deploying our apps with operators - It is very simple to deploy with `kubectl run` / `kubectl expose` - We can unlock more features by writing YAML and using `kubectl apply` - Kustomize or Helm let us deploy in multiple environments (and adjust/tweak parameters in each environment) - We can also use an operator to deploy our application .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Pros and cons of deploying with operators - The app definition and configuration is persisted in the Kubernetes API - Multiple instances of the app can be manipulated with `kubectl get` - We can add labels, annotations to the app instances - Our controller can execute custom code for any lifecycle event - However, we need to write this controller - We need to be careful about changes (what happens when the resource `spec` is updated?) .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- ## Operators are not magic - Look at the ElasticSearch resource definition (`~/container.training/k8s/eck-elasticsearch.yaml`) - What should happen if we flip the TLS flag? Twice? - What should happen if we add another group of nodes? - What if we want different images or parameters for the different nodes? *Operators can be very powerful. <br/> But we need to know exactly the scenarios that they can handle.* .debug[[k8s/operators.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/k8s/operators.md)] --- class: title, self-paced Thank you! .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/thankyou.md)] --- class: title, in-person That's all, folks! <br/> Questions?  .debug[[shared/thankyou.md](https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training/tree/2020-02-enix/slides/shared/thankyou.md)]